1st of January, 1841

Anger against the Kingdom of Poland springs deep, and from a number of sources. Its much-touted liberties, while undeniably better than those of other non-constitutional monarchies, haven’t really been expanded in centuries, and seem like a very low standard to be proud of when much better examples are popping up all around the world.

Aristocratic rule and the lack of democracy. The state treating its citizens less equally than it claims to. Ageless class differences being highlighted as people’s old way of life is disrupted and industry brings great wealth to some while driving others into poverty. And of course the violent suppression of anyone who dares to speak up. It makes sense that tensions would first flare up somewhere all these factors overlap. And as the High King so insists on presenting himself as the head and symbol of Poland, the people’s collected frustration is aimed at him as well.

The Byelorussians are a conglomeration of Slavic tribes squeezed between the Russians, Ruthenians and Poles, almost able to pass as any of them but never really viewed as their own people or given an area recognized as “theirs”. The borders of the Moscow Pact running right through their lands and splitting them between three different countries didn’t help, but the Pan-Slavic worldview was still the dominant one, so this didn't seem like such an issue. Even the Byelorussians didn’t necessarily recognize that or any other name for themselves, only identifying with their hometown or village and maybe, maybe, whichever kingdom they were part of.

(Reused image)

(Reused image)

Only recently has that really started to change, with concepts like nationalism, self-determination and cultural unity seeping their way into the countryside, at the same time that the borders dividing them are more relevant and strictly imposed than ever. Perhaps those ideas wouldn’t have taken root so strongly if life under the Polish crown was otherwise impeccable. But as matters of identity mix with everyday woes, never fully separable, they end up provoking one of Poland’s first

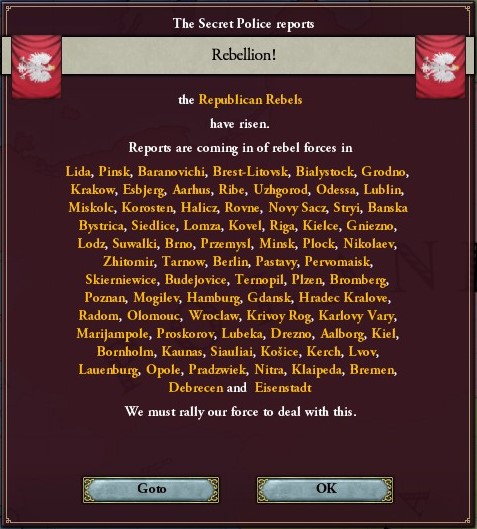

openly anti-monarchical movements in Brest-Litovsk, a mid-sized city at the western end of what could be called the Byelorussian region. The movement is leaderless and nameless, its membership small and its goals unclear, but they do include liberal, independent and revolutionary elements. Besides Byelorussians, the city is actually about 22% Polish (and 12% Jewish), adding fuel to the fire as those Polish-speakers are on average more defensive of the monarchy and not huge fans of any separatist movement in their hometown. A sudden clash between the revolutionaries and angered royalists, largely just an unarmed street brawl, is broken up by force with several revolutionaries killed, more injured, and even more arrested before the rest run away.

Poland has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to public provocation against the crown, the High King or the undivided Kingdom of Poland. The big question, of course, is how the intimidation value stacks up against the outrage. The story of what happened in Brest-Litovsk and the favoritism shown to the Polish counter-protesters is picked up and spread by local presses. Trying to cover their own tracks, the local authorities crack down on these newspapers, setting almost word for word the precedent that just reporting the facts may be punishable. In an ill-advised (and ineffective) attempt to contain the growing mess by also targeting banks, businesses and public figures suspected of dealings with liberal groups, they only dig themselves deeper, and the stage is set for a region-wide rebellion.

When the situation dawns on Krakow, the government is rightfully worried that it’s witnessing first-hand how the German and Latin revolutions might have begun. That may be an overreaction, of course: it’s not Poland’s first time dealing with some local unrest. But with Europe west of the border still in flames, smoke is in the air and no one knows where the sparks might fall. By being so harsh and absolute for so long, the crown and the Sejm have both painted themselves into a corner on this matter, feeling unable to compromise with the liberal movement if they wanted to (which they don’t). And if they can’t either accept the demands or let the protests continue, that seems to leave suppression as the only option, no matter how counterproductive.

Although, between the crown and the Sejm, the latter actually feels far more strongly about the matter. Since its formation as a response to royal abuse 337 years ago, the Sejm has always been an exclusive nobles’ club, not even meant as a house of “representation”, but its growing role as a government organ and the birth of popular parliaments in other countries have amplified demands for expanded voting rights. The ability of the

nouveau riche to “buy their way into the Sejm” has been hard enough for the nobles to swallow, but at least they’re still few and far between and their interests mostly align. In comparison, the idea of the voter base being expanded even slightly from its current 2% and bringing in the unwashed masses – or just lesser burghers – is quite unthinkable, and would utterly transform the nature of the institution. Even worse, that change being imposed from either below or above goes against the basic tenet of the nobles being their own masters and the crown listening to

them.

Of course, whatever his personal thoughts on voter reform – publicly he moves in lockstep with the Sejm – “Death to the King” is hardly pleasant to Nadbor III’s ears either.

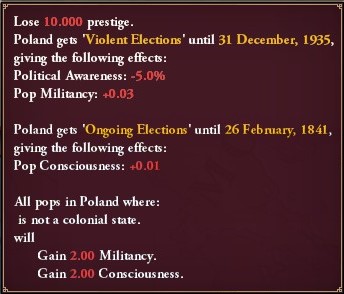

Worse, 1841 is an election year for the Sejm: normally not a very dramatic occasion, but while the nobles gather in their shadowy chambers to elect their favorite or just most generous colleagues, it’s the perfect timing for rabble-rousers in the street to rant and rave to the populace about the fact that

they’re not allowed to participate. Clearly the knock-on effects of the Brest-Litovsk farce aren’t limited to Byelorussia.

The election itself coincides with the Kupala Festival in late June, but the speeches, “debates” and other rituals start already at Midwinter. On March 10, at the same time that the New Sejmic Palace in downtown Krakow is packed full of nobles (the first Sejmic Palace burned down in 1601 at the start of the civil war), a sudden riot springs up in the streets outside. The unruly mob takes even the increased guards… off guard… and attempts to enter the Palace. Especially with all those nobles present, this cannot be allowed to pass. Given that this is Krakow, the military is readily available, and the riots are put down with great prejudice – and no lack of damage to both property and human life.

A mastermind behind the well-organized riot is soon found: the Red Eagle Army, a group flying the Polish flag with the colors switched, that threatens to turn Poland upside down in the name of mob rule. Historians will later decide that the Red Eagle did indeed exist, but at this point was only a small group turned into a boogeyman and easy target for the crown, ultimately feeding into its popularity in something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

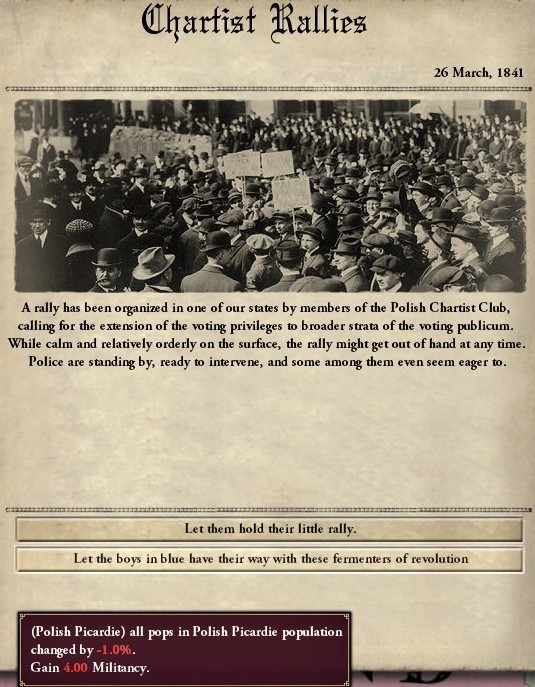

This paranoia also contributes to unnecessary violence against groups demanding voter reform in a more peaceful manner.

The election itself is rather boring in comparison, the nobles (now with extra security) almost making a point of acting like nothing’s wrong and voting the exact same way they always do. Liberal candidates actually earn a rather even 15% of the vote across the country, more with the capitalists than the aristocrats, trying to advocate for some kind of compromise to appease the people before things truly get out of hand. But alas, in the Polish system, a strong minority across the board means absolutely zero seats, and the composition of the Sejm in no way reflects the current social reality. The only sign that they’re even aware of it is the speech made by the new Premier, Wladislaw Sarna, where he vows to preserve the sanctity of the Sejm and make sure that no lowborn peasant enters these hallowed halls, at least not without a tray of tea.

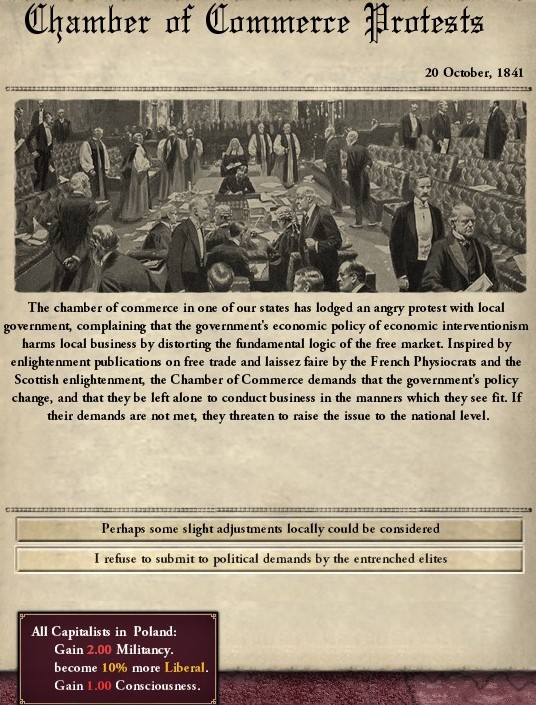

As 1841 turns into autumn, then winter, the open riots seem to have died down well enough, but the government is worried by reports that the groups themselves have just gone underground and become more determined than ever. Meanwhile, the liberal movement seems to be digging its roots into the Sejm after all: though the economic-liberal politicians’ relationship with the rest of the liberal movement is pragmatic at best, and they in fact try to distance themselves from it, there’s a certain temptation for them to throw their lot in with the reformers after all. The Sejm’s current laws are stopping them from getting elected or working towards their own agendas either.

Consciously or not, cultural minorities are considered especially suspect, turning the government’s watchful gaze to places like the German North Sea coast. Smaller strips of non-Slavic land like here, Calais, Austria and Hungary sometimes get treated less as fully-fledged provinces and more like occupied zones, even if they've been that way for centuries. As all non-government mandated political groups and meetings are illegal anyway, that just gives people good reason to be more discreet about their opinions, which is then a good reason for the government to label any and all of them as “underground seditious movements”.

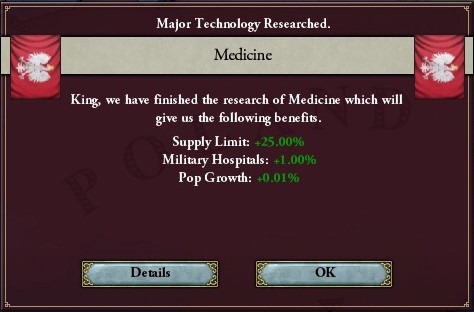

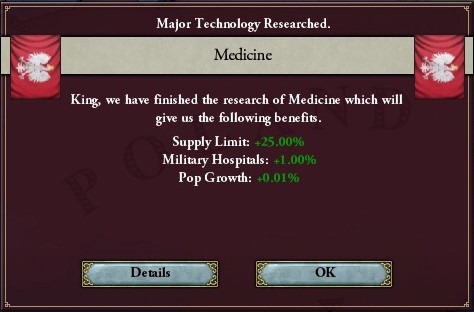

At least people’s lives are getting slightly better in other ways, no thanks to the government, with advancements in medicine extending the lives of wounded soldiers and regular citizens alike.

(Most of the game’s increases in population growth come from reduced mortality rather than increased fertility, which is of course historical. Meanwhile, Military Hospitals adds to the number of soldiers who return to the population when "killed" instead of actually dying.)

(Most of the game’s increases in population growth come from reduced mortality rather than increased fertility, which is of course historical. Meanwhile, Military Hospitals adds to the number of soldiers who return to the population when "killed" instead of actually dying.)

In fact, in February 1842 the nation acquires a new distraction: having lost its alliance with Germany, Chernigov has nothing to protect it from neighbors wanting to settle some old debts, and Novgorod for one has never given up on reclaiming the lands taken from it back in 1680 (coincidentally Byelorussian for the most part). Now it’s making its first real attempt at a comeback, and Moldavia has already pledged its support – so Nadbor III decides to do the same, thinking that allowing any conflict in the region to drag on too long would only add to the unrest. The Polish-Chernihiv relationship has been on-and-off at best, and Chernigov's willingness to coldly support the Bundesrepublik was always rather unnerving, even if it never came to anything, so the High King’s decision has plenty of support from Sarna’s Sejm.

As Polish armies march straight into the Dniepr swamplands, those new field treatments couldn’t have come at a better time.

Even beyond the difference in numbers, Chernigov is rather poorly placed for this war. Its eponymous capital is right on the Polish border, as are its most valuable regions in general, and the three Slavic powers invading it are able to do so on an extremely wide open front.

(I don’t play around with the battle plan editor that much since it has no real gameplay use, but sure, why not?)

(I don’t play around with the battle plan editor that much since it has no real gameplay use, but sure, why not?)

In Germany, the turmoil that people thought had ended already is apparently still going, with the Nationale Partei seizing power once more. The ringleader of the last coup, General-Director Ulrich Cranz, has been busted out of prison and is at it again, riding a wave of discontent caused by the Second Republic’s inability to put together a working government or make any progress in fixing the country over the past year and a half.

The eastern war doesn’t magically erase all of Poland's western problems either. The Danes, perhaps one of the most distinct minorities in Poland but usually rather well-behaved, are making noise and starting to talk about either independence or, perhaps, union with Sweden. No such ideas will be tolerated, of course, in Denmark or anywhere else.

That war, though, does go very smoothly, with the enemy apparently realizing they’re badly outmatched and letting the invaders pass almost freely with minimal fighting. Alas, Novgorod’s demands are rather significant, and it takes a while for Chernigov to stop haggling. The newly independent republic of Bolgharia – trying to reclaim its traditional lands from Chernigov – getting involved is certainly a good motivator to reach an agreement.

In August 1842 the peace is signed, returning the border to its Moscow Pact position of 1444. Novgorod actually gets a little excited and has demands for more, but Poland is the moderating presence in this case, refusing to continue the war just so Novgorod could take an eye for an eye. With Chernigov no longer distracted, the Bolghars also end up making a white peace before their opportunism can backfire.

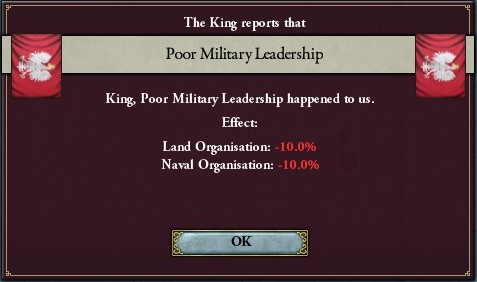

For all its apparent ease, the war wasn’t actually a very good showing for the Polish military, with a perceptive observer being able to notice a lot of deep structural flaws in how the army is organized and the officers trained. One such person actually writes a rather scathing report back to Krakow. It could well have been quite the disaster against a more equally-matched enemy.

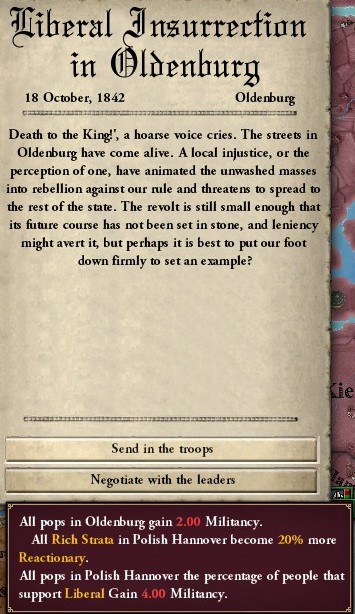

But as the military sets out to reluctantly work on these problems, the unrest at home continues. It’s clearly no longer a local problem in any sense, with occasional protests, street fights, secret societies and whatnot popping up at every end of the country in turn… though notably, mostly near the borders, making the problem less urgent for Krakow on one hand but raising the specter of some independence movements getting mixed in.

Meanwhile, paying little mind to internal problems, the Polish foreign service has been working with the treasury and a chamber of investors to perform a – surprisingly skillful – hostile takeover of the growing Lotharingian economy. As the Principality’s most valuable exports include largely the same resources such as coal and steel, the Poles have successfully bought up large portions of the local industry, become its largest buyer

and seller and entangled its supply lines with Poland’s, making Lotharingia almost entirely dependent on it (and especially its ports, lacking any of its own). The ruling Parti Nationaliste, having reacted too late to do anything about it, deeply resents this state of things. The next step in the Polish playbook is to exploit it for diplomatic pressure.

Annoyingly enough, even if the noble parliament can’t do anything, Lotharingia is also struggling with a liberal movement not unlike Poland’s, and what seems like a Polish takeover of the country is the last straw that pushes them into open rebellion. Polish influence isn’t quite at the point where it can just march into the capital without permission, leaving the troops to watch from across the border.

On the other hand, Poland’s own industry keeps chugging on as railroads, tested mostly on very short distances until now, start being adapted to actual practical use. The most ambitious project so far is the so-called Miedzymorze (“Intersea”) Line, providing a direct connection from Gdansk to Odessa and passing through several major cities on the way. At last, one will be able to pass from the Baltic to the Black Sea in just a couple days. It’s planned for industrial use at first, but growing to include passenger lines as soon as possible, revolutionizing travel forever as the web of steel spreads across Europe. Though the terrain is perfect for it, laying the groundwork and working out the kinks in the machinery is still expected to take several years. They were hoping to build a rail network connecting Lotharingia and Frisia, too…

In November 1843, the new Lotharingian constitution is signed into law, making it into a true republic on par with the others in Europe – but more problematically, the new government is determined to weed out all undue foreign influence, going so far as to confiscate Polish property, deport Polish citizens, and declare all trades or contracts with them annulled. Bold words for someone 40 miles from the border.

Citing this direct attack and insult as a casus belli, Polish troops already on the border quickly start their march towards Charleroi to protect their citizens and their rights. The war isn’t entirely effortless, as even though it was unable to stop the revolution, the Lotharingian army isn’t a total pushover. Several bloody battles follow in the countryside as the Polish commanders try to stop the newly-founded republic from regrouping and mounting a more effective defense.

It’s still wrapped up in early 1844, but Poland doesn’t actually have interest in anything as radical as a restoration of the old Principality or any kind of continued occupation, only some

assurances that its assets will not be threatened again. It does take the opportunity to deepen its influence further, of course, and by the end of it, Lotharingia is tighter in the eagle’s grasp (and more spiteful about it) than ever. The Polish Crown Railways get to dig in their grubby fingers too, gaining a near-monopoly over the fledgling Lotharingian network and the ability to integrate it into Poland's.

Germany just can’t catch a break: in November 1844, after tolerating the repressive Cranz regime for another two years, the people decide that this isn’t working out either and overthrow him – again. This should at least be a humbling example for any future would-be dictators in Germany, but the country isn’t exactly in good shape as a result of the constant back-and-forth. Many historians will consider the whole period from 1840 forward part of one long civil war.

Poland, on the other hand, seems to be doing just fine: liberals have been a constant nuisance but not a real threat for some years now, business is booming in west and east alike, the Miedzymorze and other rail projects are making steady progress. To some, of course, the subjugation of Lotharingia is just another example of royal ruthlessness, the railways just another symbol of progress (literally) passing them by: even though much of the eastern region is in any case unsuited for railways due to its forests or swamps, it is true that railways by their nature link together the major cities while running through forests and fields and disturbing the countryside. Anti-railway protesters clash with those wanting to fix these same problems by adding

more railways, but eventually they decide to just join forces against the current policy-makers and figure it out from there. They then end up getting recruited by the wider liberal movement, willing to pick up whatever subject it can bash the government for; in this case, demanding representation in the Sejm so that the people can decide where the railways are or aren’t built.

The largest such protest at the construction site of the Krakow Central Station, December 1844, turns into another riot. As first the railway security and then the military answer with violence, word spreads quickly and similar groups in other cities spring to action. Somewhere these are just overgrown protests, not a threat even to the local troops, but in some places – especially along the Miedzymorze – there’s a real insurgent uprising, surely orchestrated by the Red Eagle.

Likely due to having started so suddenly, the haphazard revolution is nowhere as large as it could’ve been, but putting it down still takes several months of heavy-handed military action and one-sided trials, and even then, most of the rebels just flee into the countryside or take off their armbands and pretend they had nothing to do with it. Actual fighting having started over such a seemingly minor issue, and the military responding so harshly, sends people a message – and not necessarily the one the crown would like.

Not just that: with the great powers too busy tripping over their own feet for a while now, life across the Atlantic has been rather peaceful, but the sheer mix of incompetence and tyranny in Europe in contrast to the relative prosperity of Amatica is just adding fuel to old ideas of colonial independence. The failed Amatican Revolution of 1776 already had a distinctly liberal flavor, even before the same ideas really hit it big in Europe, and this is clearly feeding back into “liberty” becoming synonymous with Amatican identity.

And while similar movements pick up speed elsewhere, the situation is exacerbated by a particularly bad harvest in some of the already poorest and most restless regions, which the government for once does its best to alleviate. Still, the economy in general has definitely taken a turn for the worse, with workers out on the barricades and investors unwilling to invest in something that could be torn down by an angry mob the next day.

It’s hard to see what the government’s endgame is here, though. After the crackdown on the Railway Rebellion only caused sympathetic liberals to start arming themselves with renewed fervor in preparation for Round 2, the hardline stance doesn’t seem very sustainable. Besides, not even the Sejm – or most of it, at least – is actually enthusiastic about the idea of shooting and beating Polish citizens en masse from here to eternity, yet the increasingly ingrained attitude of “Liberty or Death” might force them to do just that. Premier Wladislaw Sarna, however, is both tied to his word and still a firm believer in it, and under his leadership, the Sejm isn’t going to budge. He seems to have Nadbor III's tacit support.

And indeed, on that front, some people cling onto hope that even if unlikely to propel the liberals into power, the upcoming election of 1846 might at least make the conservatives see reason and put someone more moderate in the Premier’s seat. They don’t get a chance to test that theory, for on 18 March 1846, a new country-wide uprising finally occurs: this time without a particular provocation, clearly planned and organized by someone. The army is once again put on full war footing, and Yugoslavia also dutifully sends in troops to help. At least it seems like the liberals haven’t managed to infiltrate the military itself, as was the downfall of Italy.

The uprising is accompanied by separatists in Hungary, Slovakia and Ruthenia as well. But as tempting as it is to paint the Red Eagle Army as the enemy and this as a civil war, calling upon memories of the Confederates, it is clearly an attempted revolution, with the state going to war against a disparate mass of its own citizens. And though they are mostly disorganized, scattered and no match for trained soldiers, on the few occasions that they manage to group up into a larger army under a competent commander, they actually manage some real victories – sure to go down as heroic struggles for liberty. But all in all, there are always more soldiers to come, and pluck and panache can only carry the rebels so far. Their defeat (for now) is only a matter of time.

At this point, no amount of self-deception can claim that the situation could be solved just by waiting or beating at it until it goes away. As the delayed election proceeds in war-like conditions, Premier Sarna’s handling of the liberal movement comes increasingly under fire, mostly ignoring the fact that most of the Sejm supported it and him until just a while ago. Over the summer and early autumn, the uprisings are once again “put down”, but everyone knows that only means waiting for the next ones, and candidates on both extremes realize they might actually have a chance of taking some usually moderate seats this year. The Crown Council, too, has been swinging more towards the liberals lately, and there’s a chance it might be willing to pass some reforms with or without the Sejm’s support.

Indeed! For the first time since anyone started counting this kind of thing, the “conservative” deputies don’t even break 50%, with the liberals coming in as a close second. It’s hard to draw any geographic trends, the results clearly coming down to each individual district, but that just means the shift is countrywide and even more significant. With these two factions competing for the top, the reactionaries get to play kingmaker in a sense, but there’s no question that they support the conservatives over their sworn opponents the liberals. This still changes everything, though: the middle-of-the-road moderates, who had arguably been swinging rather authoritarian during Sarna’s term, are going to have no choice but to work with either extreme if they want to get things done – but making concessions to

both seems like a lost cause, and sticking too close to the reactionaries would just mean continuing the clearly ineffective policies used so far. A moderate-liberal alliance seems like the only option.

As “party” politics become more relevant, despite parties not technically existing in a legal sense, their respective names also start getting thrown around a lot more, and the limits of that law are going to be tried quite a bit. And unsurprisingly, due to liberal demands, the Sejm submits a request for Nadbor III to declare a loss of confidence in Sarna, who is replaced by the far calmer, more “reasonable” Mariusz Nowak.

The effects of both the new Premier and the changes in the Sejm are immediate. The tone of discussion in the chamber changes radically – for one, the Coalition and Populists really are

discussing things, even if there’s also the Royalist contingent shouting from the rafters. New orders are given to the military and local authorities not to crack down on protests and liberal groups quite so quickly, but to either let them march in peace or point them in the right direction to complain. Of course, that still falls short of actually

enacting those changes they demand… but it’s still a first step.

Alas, fate is a cruel mistress, and just as this all-new government is starting to think that everything’s going to be alright, it is immediately put to its greatest test.

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote