Results 121 to 150 of 313

Thread: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

-

2019-09-04, 11:20 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- Earth and/or not-Earth

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Based on recent history, I think it would make the most sense for Poland to concentrate its territorial expansion in the colonies - perhaps try to force out every other colonial power in the regions you've expanded into. Alternatively, you could try to put an end to the rise in conflict between Moscow Pact states, either by siding with the defender in any inter-Pact war or by vassalizing them all. After all, Poland is the defender of Slavdom, and sometimes that means defending Slavs from each other.

Last edited by InvisibleBison; 2019-09-04 at 11:21 AM.

-

2019-09-04, 11:35 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2005

- Location

- Zagreb

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

There are a group of Slavs not protected by the Moscow pact, the South Slavs. The time has come to free them from their allegiance to the pope and other catholic states (and get good vacation spots on the Adriatic).

-

2019-09-07, 01:02 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

I'm inclined to recommend taking over Indonesia, though I don't know how much benefit Poland would gain with the way trade nodes are set up. Maybe go for some

unrestrained colonialismglorious imperial conquest in Japan/China later on?ithilanor on Steam.

-

2019-09-23, 02:24 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Just popping in to say that I haven't abandoned this: my summer vacation just ended, leaving me with less free time, a lot of which is taken up by other hobbies and obligations. I'm still trying to get updates out every now and then, hopefully sometime this week, but some level of slowdown will definitely persist for the time being.

-

2019-11-15, 07:03 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Any news on this? Curious how our favorite alt-history wacky Poles are doing.

ithilanor on Steam.

-

2019-11-22, 06:37 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

I'm afraid it's definitely slipped into another unplanned hiatus due to me being distracted first by schoolwork and then, full disclosure, stuff such as other games too. I tend to get kinda monomaniacal when I do start updating again, but that just means it's even more time-consuming. I'm not burned out or bored with the game itself, though, so an update will definitely come when I find the time and energy.

-

2019-11-22, 11:42 AM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Location

- Massachusetts

- Gender

-

2019-11-23, 12:39 AM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

ithilanor on Steam.

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

ithilanor on Steam.

-

2020-01-07, 03:22 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #40: Going South (Stanislaw II, 1685-1695)

Spoiler: Chapter9 May, 1685

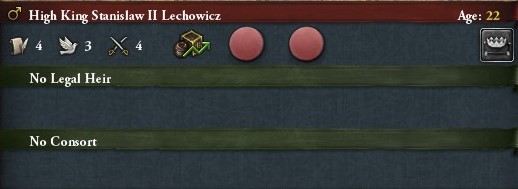

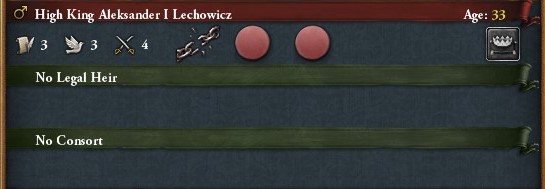

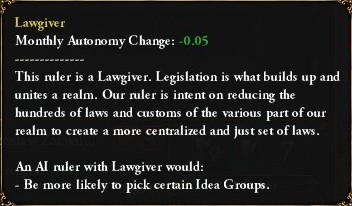

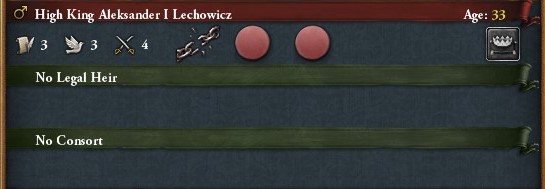

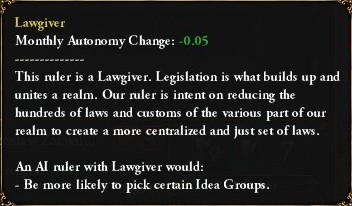

Despite being something of an emergency replacement after the accidental death of the previous heir, Stanislaw II ended up having a full twelve years to learn the craft and grow up into a fine monarch. Like many Poles these days, he’s quite globally and economically minded, already bursting with ambition to continue Polish expansion in areas where he feels it’s been lagging.

The heart of Poland’s colonial empire is of course in Amatica, where the three voivodeships of Buyania, Lukomoria and Jeziora combined far overshadow mainland Poland in terms of area, though obviously not population or wealth, and almost resemble nations of their own with unique melting pot cultures. The south of the continent is dominated by the Asturians (and their conquered Andalusians, who have fled to the colonies en masse, but also have their own stronghold in the far west Kalifania), and there are places where the border could bear to be adjusted a bit; however, there’s plenty of “unclaimed”, a.k.a. native land to give both sides plenty of space without having to go to war directly. This region is in fact not Stanislaw II’s top priority.

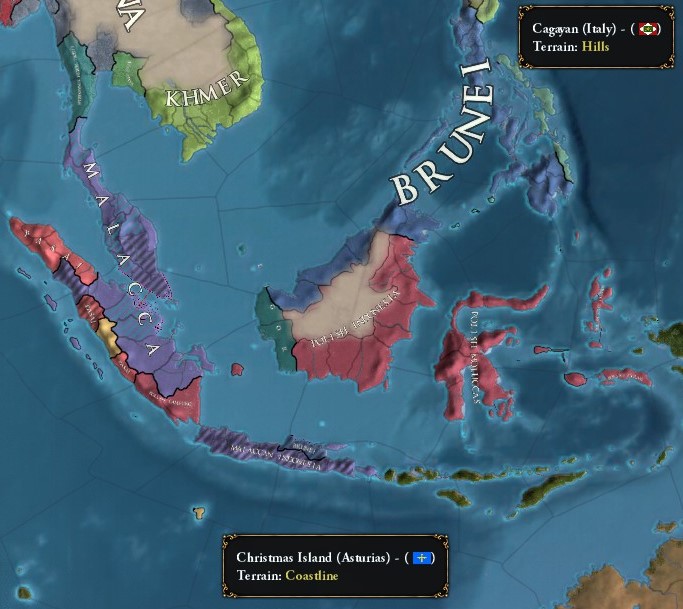

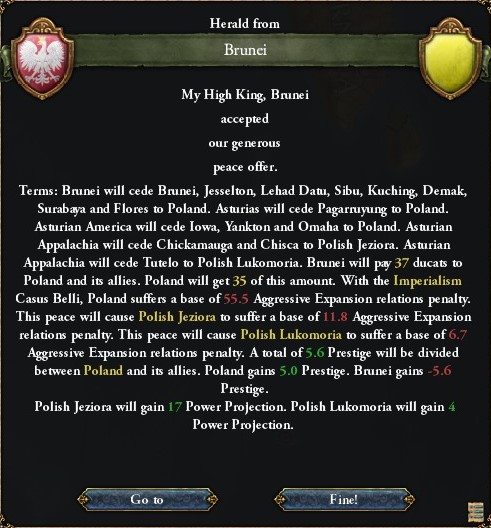

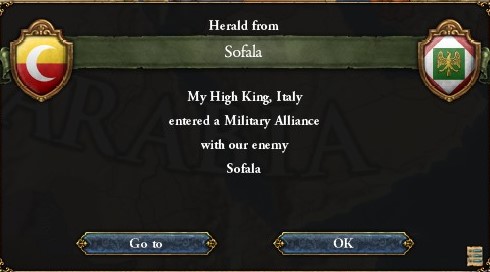

His eyes aren’t on Africa either, which the Poles largely treat as an oversized rest stop, but the East Indies. The last farce of a war against the Sultanate of Brunei showed that the local states aren’t to be underestimated, but also their potential value if added to the colonial empire. Poland is by far the dominant European power in the east, but Italy and Asturias have also acquired bothersome, if still small, outposts of their own, and could quickly gobble up Poland’s potential targets if left unchecked.

The East Indies are also important as the pathway to Stanislaw II’s other passion project: the new continent to the southeast. He’s been following the settlers’ progress intently since they first made landfall a few years ago, and though the coastline has been quite thoroughly mapped, the sheer scale of the inland wilderness boggles the mind. Who knows what sorts of treasures it might hide – the settlers have already found plenty of mineral riches, if not necessarily a literal city of silver like in Alcadra. However, even as the Poles have clearly claimed the continent itself (and tentatively named it Nowa Straya), the Italians have set up a pesky little base here as well.

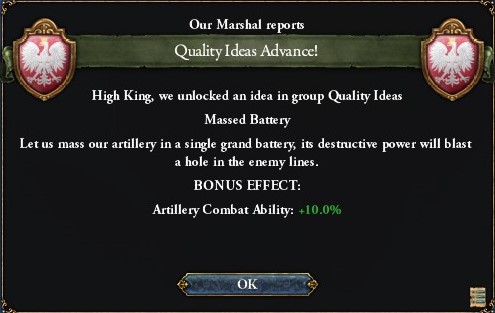

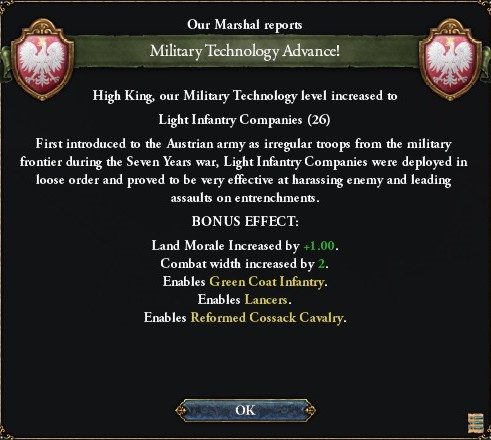

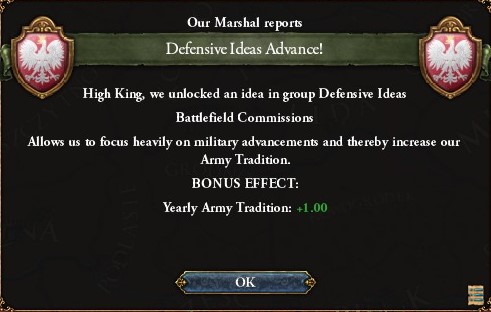

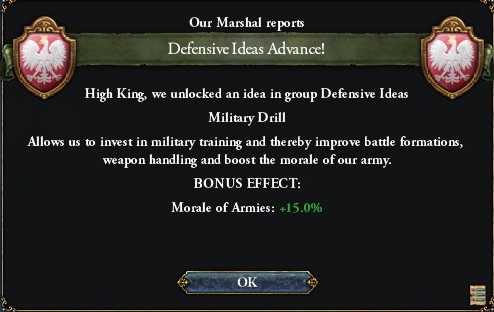

As Poland gears up for a new wave of conquests, though, Stanislaw II first focuses on laying the groundwork at home. This massive expansion of Poland’s military manufactories is targeted not just at its European provinces, but the colonies as well, as being able to produce supplies at the front obviously makes logistics a lot easier.

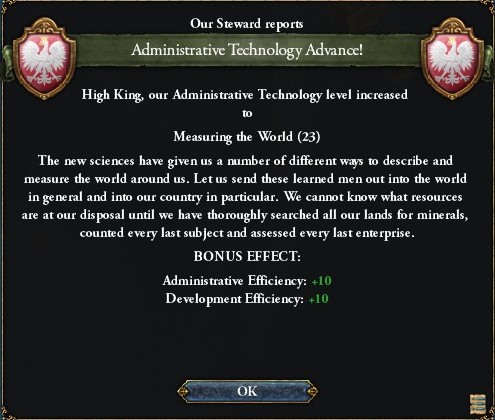

And so, as Poland’s understanding of the world, its shape and its political realities grows ever deeper, it becomes easier and easier to – intentionally or not – start thinking of countries and continents, people and nations, simply in terms of precisely calculated numbers and resources to obtain and exploit…

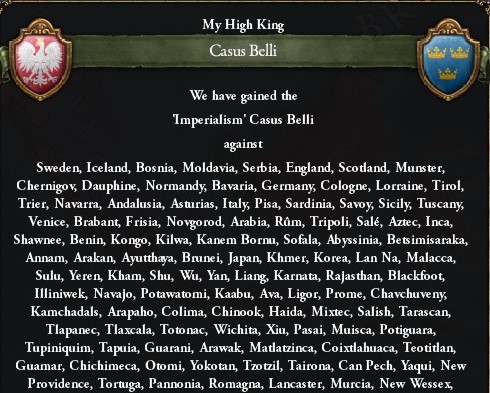

It would be silly to claim that the ‘justness’ or ‘righteousness’ of their wars has ever been a conqueror’s first priority, but it’s never been mere empty talk either: what is considered a fair reason for war by the people waging it, never mind everyone watching, changes on time and place and always somehow reflects their values, even if in the end it is mere rhetoric. For most of Polish as well as Christian history, religious rhetoric has been the most popular of all, but in the wake of Europe’s increasingly confusing political situation and the writings of certain Renaissance writers, a certain philosophy is putting into words what many people have believed since time immemorial:

Might makes right. Success proves justification. The fact that you’re able to invade and conquer someone shows that you have the right to do so. Not that the people being invaded usually agree.

This philosophy certainly appeals to High King Stanislaw II, one of its loudest advocates even above the other Poles. The first such recipient of Polish mercy shall be the Sultanate of Malacca, the other major power in the East Indies besides Brunei. Presently under attack by Ligor and all kinds of rebels, it’s clearly unfit to take care of itself or its citizens.

That war shouldn't be much trouble, becoming a de facto proving ground for newly developed armaments and tactics as well.

Since it’s neither necessary nor even possible for Stanislaw II to personally direct that war, though, his attention is pulled elsewhere. Besides the overall burst in imperialist thinking, there’s been a recent uptick in Polish interest in their southern neighbors – the South Slavs, or Carpathians as they’re sometimes called, not deserving of the name Slav. Stuck on the wrong side of said mountains, they were conquered and converted by monotheists long before the Slavic Church could even be founded, thus basically separating them from the wider Slavic community forever. However, while culturally Slavic in some ways and vastly divergent in others, their awkward position has often made them distrusted on both sides of the religious divide and the South Slavic region a strange borderland, seldom as important as either Germany to the west or Moldavia to the east.

The main South Slavic power at the moment is the Princedom of Pannonia, part of the Francian Empire but Lollard in faith, which has recently been on a conquering streak against its weaker neighbors. However, practical and “cultural” interests alike have started to demand that the South Slavs be at long last liberated and reunited with their brethren. It’ll take a lot of adjusting for them, of course, but they’ll see that they’re better off in the long run. Poland, meanwhile, wouldn’t mind having a stronger presence and maybe even some ports in the region, often critical in its wars against the Franks. It could also be seen as a symptom of Poland’s loss of hegemony over its fellow Slavs and former vassals: just go acquire some new ones.

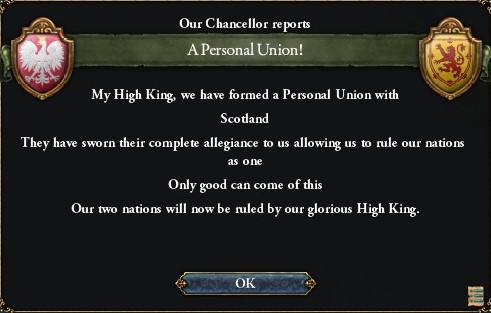

Polish envoys politely inform their Scottish allies that being too close with the Pannonians might not be a very good idea these days. After all, Poland is the one who came to the Scots’ aid when the German-Pannonian war in 1663-67 threatened to ruin them entirely. They seem to take the hint.

War is declared in August 1687. First will be the Pannonians. Then the Croats, Bosnians and Serbs.

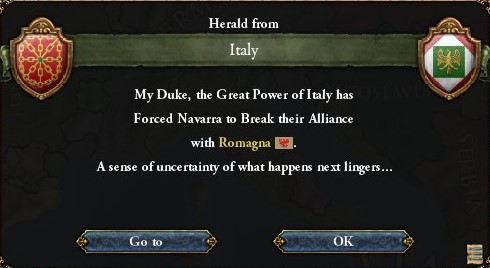

The Emperor in Navarra is too weak, too bankrupt and on too bad terms with Pannonia anyway to interfere in the war. It thus looks like another unresisted cakewalk.

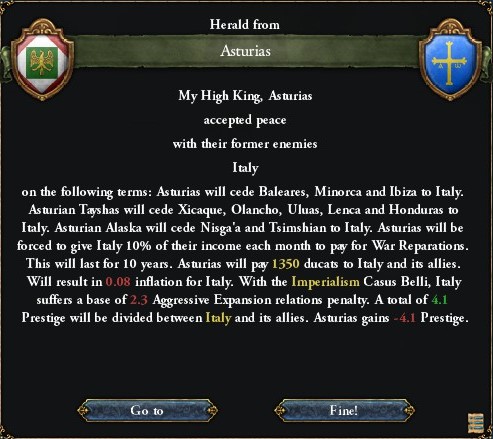

However, if the Poles think they’re conquering lots of territory just by rolling down into Pannonia, the Swedes have them beat by far. After a long and painstaking war, made difficult by the sheer amount of far-flung territory being fought over, King Alf II of Sweden forces a momentous peace treaty on the ever-dwindling Andalusians that includes the transfer of nearly all of Andalusia’s Alcadran colonies, including the strategic isthmus in the north and the vast Narafidian provinces in the south. Andalusia was the very first to discover and settle that continent, but now it only holds on to a few scraps, while the vikings of all people control the largest piece of it by far.

In any case, the Pannonians retreat south and hide for as long as they can, but when it becomes clear that this is achieving nothing, they make a glorious last stand against the Polish troops under Trojden Zaluski (grandson of the Trojden ‘Madman of Mazovia’ Zaluski who got himself famous in the Confederate Civil War). With their backs well and truly broken, they scamper off once more and leave the Poles to their bloody work of ‘liberation’. Although, having clearly already won, the Poles try to be a bit more light-handed from here on.

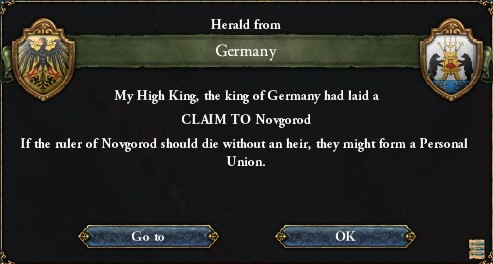

Germany seems to be in the mood for some Slavic consolidation as well, seeing as how King Leszek II Lechowicz declares himself the prospective heir of his cousin, King Andrei IV of Novgorod. His claim is indeed legitimate (not counting the terms of Moscow Pact), but Andrei is still young and simply hasn’t had time to have children of his own yet; however, should something happen to him, this could create either a nearly Pan-Slavic union with Germany, Vladimir and Novgorod all under one crown – or start another great Pan-Slavic war.

The invasion of Malacca is brought to an undignified end in June 1688 as the East India Company annexes most of Java, the southern tip of Malaya and various outlying islands; it’s the most they feel comfortable taking without overextending themselves or clashing with the other local rulers for now, but will serve as a springboard for future conquests. Poland is now the clear master of the lucrative spice trade, and overlord of an increasing number of Muslims and Hindus.

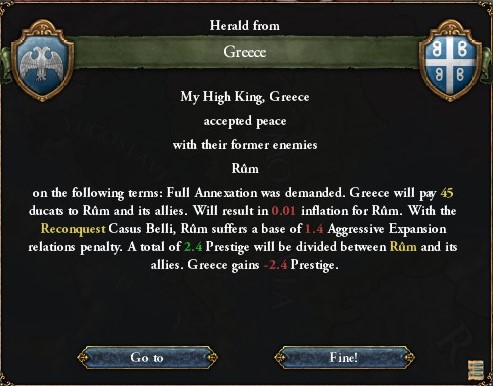

Some months later in November 1688 comes the far more dramatic Treaty of Kaposvar, which brings the annexation of all of Pannonia’s Slavic-majority provinces, as well as the cities of Laibach and Wien because of their important location (and great value). One Hungarian province is handed over to Moldavia. However, besides Wien which is combined with the previously conquered Ostmarch, Stanislaw II doesn’t consider it either practical or necessary for Poland to govern all the South Slavic lands directly.

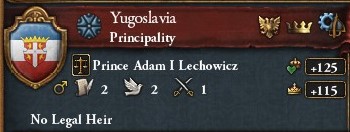

Instead, his plan was always to create another autonomous state that would take care of its own business while securing Poland’s interests in the area. He likes to compare it to Frisia, which has been a relative success story so far, but the ancient (and horribly failed) Congregation of Germany might actually be a better comparison: an artificial pagan state imposed from above on conquered Christians, with only the thinnest veneer of legitimacy. To undermine the local elites, he doesn’t place the court in the Pannonian capital of Pecs, but rather the nearby Kaposvar where the treaty was signed. In hopes of making it a cultural union of all the South Slavs, this state is named the Principality of Yugoslavia... 'Land of Southern Slavs'. Unlike a voivodeship, it'll be a hereditary position held by a Lechowicz line, but not on the level of a Grand Duchy due to the Sejm protesting against it.

Stanislaw II has no illusions about how his Christian cousins are going to receive their new pagan overlords, especially in the short term; however, even if the most ambitious dreams of Slavic unity prove impossible to ever achieve, at least Poland can reap the practical benefits. He plans to continue farther south as soon as the Yugoslavian state has been stabilized.

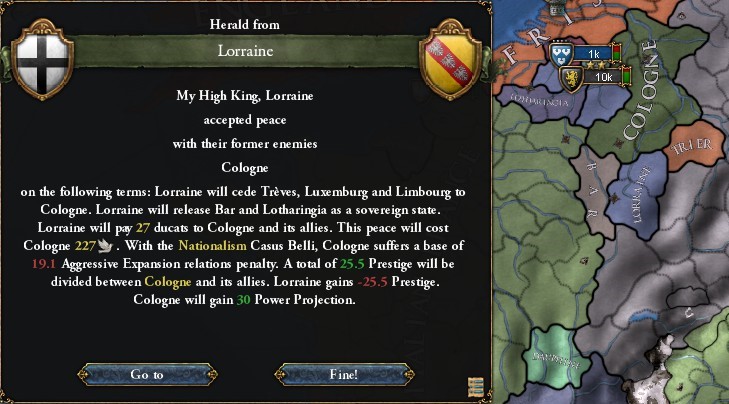

There's no immediate reaction of terror or disgust from the rest of Europe, beyond that which they feel towards the Poles to begin with. Soon after, Lorraine finalizes the annexation of the last scraps of Lotharingia, removing the last independent Karling rulers from the map – though obviously some members still remain wealthy and influential within other countries. It's a good reminder of just how cutthroat European politics truly are, with or without some shallow excuse.

Germany is also perfectly happy to pounce on Pannonia and try to grab what’s left of it. This isn’t really a problem from Poland’s point of view, since the Austrian provinces in question are largely German-speaking anyway and thus don’t really fit into the Yugoslavian dream.

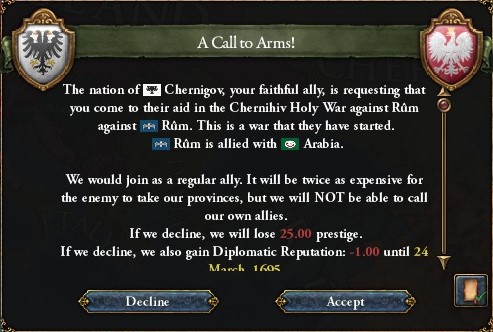

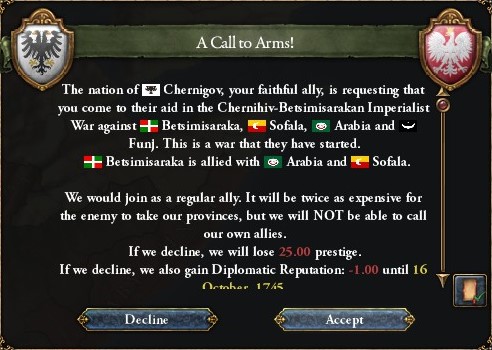

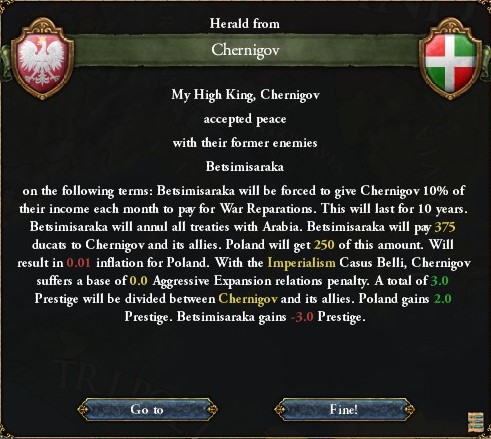

The conquests of Malacca and Pannonia were both pleasantly easy and low on casualties, too, leaving Poland in what should be great shape for more conflict wherever it can find it. As it turns out, that ‘wherever’ might be a bit away from its own borders again, for in April 1690, its close if somewhat cordial ally the Kingdom of Chernigov requests help in its war against the Muslims down south.

The Poles still have no special grievance with the Muslims, but have gotten used to fighting them by now due to their proximity to Moldavia and tendency to get tied up in European politics. Naval dominance has made them quite easy to deal with on the defense, but having to take the fight to them – into vast, unknown and infamously difficult territory – might be a different story. Still, with its friends among the Slavs dwindling, Poland can’t afford to lose the allegiance of Chernigov, so war it is.

The autonomous Moldavian army and Yugoslavia’s hastily cobbled together militia are given orders (or rather permission) to stay back and protect their own territory from enemy raids, letting Poland focus on the offense. The Black Fleet moves to block the Sea of Marmara as usual, while the armies begin their long trek south. At first, the High King is expecting to stay home and take care of politics like he did until now, but there’s actually a surprising amount of grumbling about him starting all these big wars yet not taking responsibility by leading his armies in the field like a true Pole should. Without any further ado, he puts on his armor, straps on the Axe of Plusdwa and joins the convoy. He likes to think he’s not a half bad commander himself.

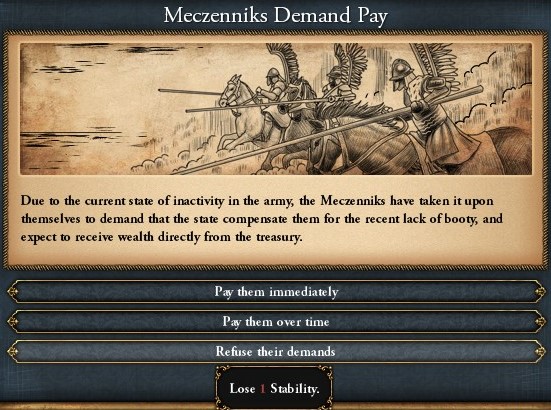

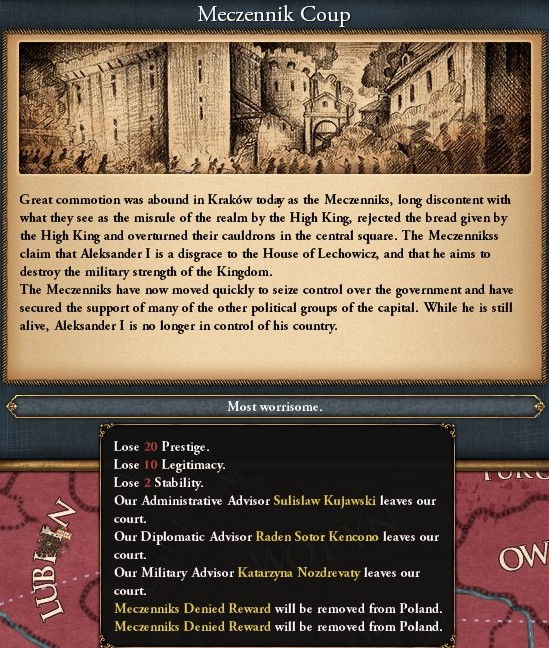

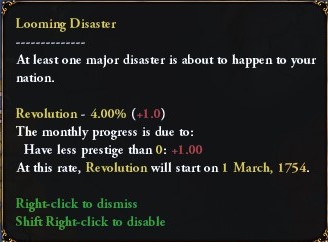

One would hope that the Polish bureaucracy could handle routine matters in his absence, but that doesn’t seem to be the case, and it seems like his “reckless” foreign policy has its detractors as well, causing trouble with setting up the Yugoslavian puppet state and getting people to accept or at least acknowledge its existence. There’s also been major uprising in Wien which part of the army must stay back to suppress.

(What’s with the typos in these specific events?)

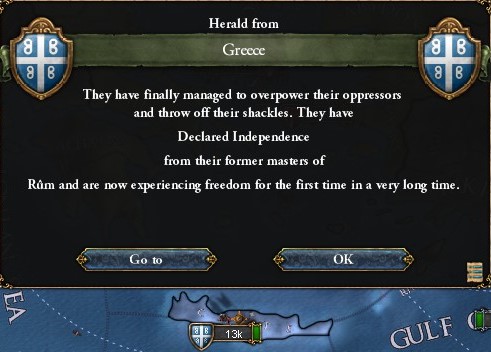

The war itself gets off to another good start, with the Poles rolling in pastConstantinopleLechogród and into undefended Rûman territory, the enemy army being busy fighting Chernigov farther east. On their way in, though, they get a good look at just how effectively the Rûmans have Arabicized the former Byzantine Empire, using conversion work and resettlement to make their religion dominant throughout Anatolia and changing the place names as well: Smyrna to Samirana, Ancyra to Anqara, Archelais to Aksari and so on. Not that Poles don’t do the same, of course. Greek also remains the majority language of the people for now, though Arabic is used in the administration.

After a bit of probing and no clear counter-attack, Stanislaw II decides to make use of the opening and drive his army towards Adana, the Third Rome itself. On the way there, though, he in fact manages to find the Rûman army – or vice versa – and ends up caught in a battle that he, for all his supposed tactical acumen, cannot win. He manages to cause some respectable casualties to an army twice his size, but is driven back nonetheless.

The Chernihiv back-up on its way to bail him out manages to get caught in the exact same trap he did, only to be rescued just in time by another wave of Polish back-up. The Slavs emerge humbled and more cautious, but victorious nonetheless.

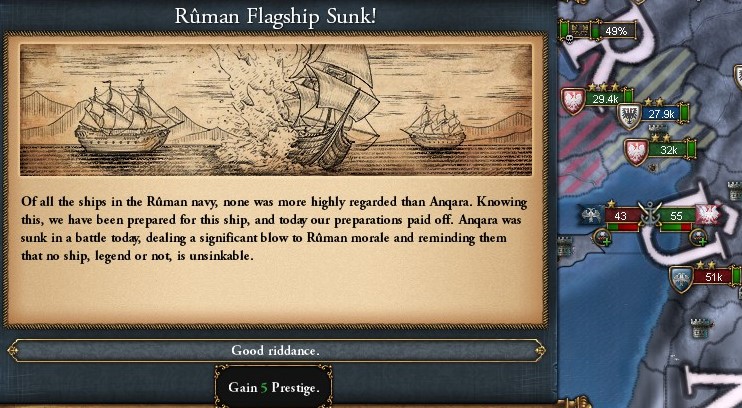

Still, because of this whole mess, the Chernihiv end up beating him to Adana. No matter, as long as someone takes it. When the city is captured and the Rûman navy driven out of port, the Black Fleet gets perhaps its first real chance to shine as the Arabian navy rushes in to help and one of the largest sea battles in Mediterranean history begins in the Gulf of Cyprus, New Year’s Day 1692. The Rûman navy is impressive, but the Black Fleet earns great glory by managing to send its imposing flagship to the bottom of the gulf.

Frankly, looking at the numbers, it’s nothing short of a miracle that the Poles’ victory is as overwhelming as it is. There will be much feasting and toasts to Kupala tonight. The Black Fleet decides to take a break while it’s ahead, though, and return to Crimea for replacements and repairs. Much of it is barely keeping afloat.

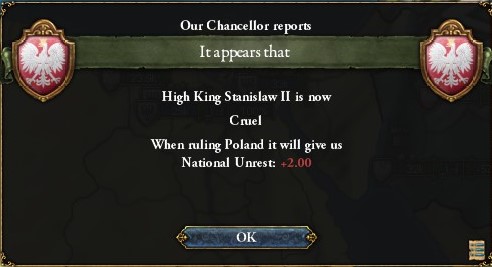

Through several more battles, the Muslims are forced to retreat south and leave the Slavs to conquer their way across Anatolia, but it’s slow going with the heavy fortifications and mountainous terrain. When their supplies start to run low, or even just because, especially the less disciplined parts of the Slavic armies often take what they want from local towns and villages with or without permission from above. Stanislaw II doesn’t see much point in stopping them, though. Lets him save money on salaries.

One army, however, wanders off into the Armenian mountains and is never seen again. Rumors spread that they’ve been caught in a massive ambush and wiped out to the last man, even the few survivors chased down and tortured to death by the vengeful enemy. Rûman general Dervis Gümülcineli, effective but obviously highly brutal, is later painted in Polish folklore as a literal mountain demon who supposedly left the whole region littered with mutilated soldiers.

When the High King hears of what happened, the Poles immediately drop everything else and convene on the area to avenge their 32,000 dead brethren. After the initial victory, what follows is a long series of battles over the spring of 1693, in which the surviving Rûmans keep desperately skirmishing and running around the mountains trying to escape. However, they’re surrounded by occupied territory and it’s only a matter of time until they and their commanders meet the same gruesome fate as the Poles supposedly did. Gümülcineli, demon that he is, still manages to slip away by transforming into smoke.

Though their honor’s been restored, this war has turned out surprisingly expensive after all and also stoked a whole new kind of anti-Muslim sentiment where they used to be the one neighboring religion the Poles didn’t mind too much. Never mind that the Slavs are actually the attackers in this whole war. Although, despite that righteous fury, this whole incident seems to have sharply reduced their enthusiasm for the war, and they end up taking a much more passive, occupying role while entrusting most offensive operations to Chernigov. Stanislaw II remains at the front, though, to support his troops, setting up camp in Damascus and trying his best to keep track of any news from Krakow, though all seems relatively quiet on the home front.

Even if victory is inevitable, though, this unnecessarily extends the war, so by late 1694 the High King decides to join the King of Chernigov in hastening the occupation of Egypt so the Poles can actually go home sometime.

In February 1695, the army under Stanislaw II takes Alexandria – basically Arabia’s second capital besides Mecca – and smaller detachments are sent out to establish control of the countryside. They have subzero interest in wandering any deeper into the infamously vast and barren deserts of the vast Arabian Empire, though, so Chernigov basically receives an ultimatum to get the peace deal over with.

That is finally achieved in November 1695, when Chernigov walks away with a lot of Anatolian and Armenian land watered with Polish blood, and Moldavia also receives the once great city of Smyrna/Samirana for its troubles. It doesn’t really feel proportionate to the sheer amount of work it took, though, and Stanislaw II isn’t going to have the warmest welcome waiting for him back in Krakow.

However, they might be up for a surprise as well, as five years on the unusually brutal front enforcing his unusually cold-hearted approach have brought to the surface a far less pleasant side of the formerly jovial monarch, now 32 years old and still in for a long reign, but scarred in more ways than one. It might be that when he starts streamlining Polish society to his optimized vision, the ‘human’ side of human resources may find itself increasingly backed into a corner…

Spoiler: War & Map Highlights(I’ve decided to cut down on war “highlights” about less dramatic wars, since for some reason these are one of the most tiresome parts to write right at the end of an otherwise ready chapter)

Slavic Holy War for Anatolia (1690-1695)

Chernigov + Poland vs. Rûm + Arabia

Chernigov requested Poland’s aid in its invasion of Rûm and Arabia, the two greatest Muslim powers. Despite several tactical mishaps and lost battles, the war itself got off to a winning start with Stanislaw II himself at the head of the troops. However, the clear low point of the war was the mutual Massacres of Mush, where first a Polish army was ambushed and destroyed in the Armenian mountains and then the same was done to the Rûmans in retaliation, involving the killing of tens of thousands of captured or wounded. The following occupation took the Poles and the High King as far south as Egypt. While the treaty failed to secure all of Anatolia, which was a long shot from the start, it did secure the last bits of the Black Sea coast and greatly expand the Slavic buffer in Anatolia and Armenia.

- Germany-Vladimir, which is quickly shaping up to be one of the major powers besides Poland and Italy (and on hostile terms with both), has annexed the rest of Pannonia and recently started an invasion of Lorraine. The King of Novgorod has gotten some children of his own, meaning that another succession war shouldn't be imminent but the tension remains.

- Sardinia is as ever in a constant state of flux, gaining land on some fronts while losing it on others (and currently under attack from Serbia).

- Between Asturias and Kanem Bornu, Andalusia’s days as a state are well and truly numbered, but there’s a massive number of Andalusian Muslims living across the Atlantic.

Spoiler: CommentsThe Imperialism casus belli is so weird. I don’t think there’s any historical reason in particular for it to be in there, it’s just to shake things up in the late game. “Nationalism” being unlocked in the late 1600’s is even weirder, but that’s mostly just the name, since all it does is give you a tool to unify your culture group. Which we already have.

Anyhow, back at it again! I once again decided/had to reread the entirety of the AAR just to remember exactly where I was, which took surprisingly long but also helped me get hyped up to continue. In a perfect world I’d be able to update, say, on a regular schedule of every couple weeks, but unfortunately the way time and motivation works seems to be closer to rapid bursts with longer breaks instead. Anyhow, I’m still on the 1.28.3 patch (before the Manchu Update) to avoid compatibility issues, and nothing else should’ve changed either.

I need to get my bearings again, decide where I’m gonna go from here and possibly do some additional modding related to that. I’m still dealing with university, other projects and such, though, so hopefully the schedule from here will be along the lines of “every now and then”.

Some things on the to-do list, besides reacting to the AI:

- Expand Yugoslavia down into Kosovo. Macedonia and Albania remain solidly Greek in this timeline, though ignoring that and conquering them anyway would probably be on-brand…

- Keep mopping up the East Indies. Possibly drive the other Europeans out, though on a meta level I don't mind their presence.

- Decide what we’re doing with Moldavia. The union isn’t going to break on its own, but we could plausibly just roleplay a reason to cut them apart manually (…again). Maybe this time on their own initiative. On the other hand, since we can reduce the balance impact of their military contribution by just telling them to stay on the defensive, it’s not 100% obvious whether we need to. Puppets aren’t terribly gamebreaking in Vic 2, either.

- Preferably deal with Rajasthan somehow (I’ve considered simply occupying them and letting separatist rebels do the rest), but even though I’d likely win numerically speaking, a continent-wide invasion front feels both unrealistic and like a nightmare to play. It’s not gonna get any better in Vic 2, though…

Input is appreciated! And as usual, feel free to ask for status updates on any part of the world and all that.Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-01-08 at 04:34 AM.

-

2020-01-07, 04:10 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- Earth and/or not-Earth

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

I'm glad to see this excellent AAR resume.

Why do you feel a need to do something about Rajasthan? Looking over the past few updates, they don't seem like much of a threat to Poland.

-

2020-01-07, 04:56 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Oh, just on a meta level, really. The continent-sized orange blob annoys me as a matter of principle.

Though partly for that same reason, you're right that it's hard to justify putting the effort into invading them.

Though partly for that same reason, you're right that it's hard to justify putting the effort into invading them.

Though if anything, it is kinda amazing how irrelevant (and seemingly weak) they manage to be despite their size.

-

2020-01-08, 10:06 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Haven't read the update yet - I'm going to reread a bit to remember what's going on - but it's great to see this come back!

EDIT: Caught up. A few comments:

- I didn't realize how far inland the Polish Amatican colonies went; that's impressive.

- "Nowa Straya" made me chuckle.

- I'm almost sad to see that a succession war over Novgorod isn't a possibility; that would've been fun to see.

- Interested to see what becomes of all the Andalusian pops in Vic 2.

- Rajasthan feels like it'll have major rebel troubles in Vic 2, though I don't know what its demographics are like. Maybe just let it fall apart then, sort of analogous to the Ottomans in our timeline?

Last edited by IthilanorStPete; 2020-01-09 at 08:34 PM.

ithilanor on Steam.

-

2020-01-17, 09:21 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #41: Age of Empires (Stanislaw II, 1695-1711)

Spoiler: Chapter24 November, 1695

Stanislaw II might still have a long reign ahead of him, and not necessarily one his subjects are going to enjoy. At the time he took the throne, his promises of expansion in the East Indies and especially Yugoslavia were met with roaring popularity – and success – but the aftermath of the latter has turned out to be more complex than expected, not to even mention the long, bloody and expensive war against Rûm that may have also been a victory but seemed to bring Poland little direct benefit (Moldavia, which gained Smyrna, is treated as the separate country it practically is. Chernigov, though currently an ally, is seen as a potential enemy at the drop of a hat). Not to even mention that he’s returned from said holy war more than a bit changed himself.

He isn’t a particularly proud man, so he isn’t so much disappointed or angered by the lukewarm reception he gets on his return to Krakow just in time for the winter solstice festivities as he is concerned. If people’s faith in him or his decisions falters at the first hint of gritty reality, well, he has his work cut out for him.

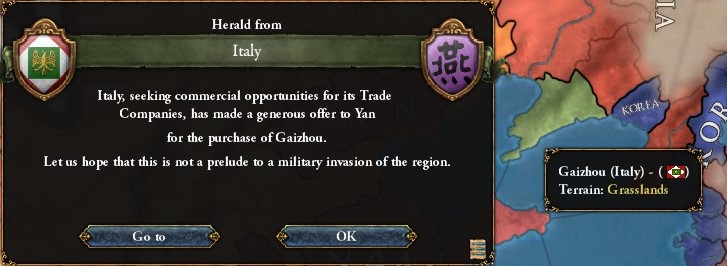

In the far, far east, about as far as you can go before ending up west, a different imperial power stirs: the Japanese Empire, in effect led by a military dictator known as the Shogun, has stayed in relative isolation for the past 160 years after first securing some ports and tributaries on the mainland, only to now finally awaken to the same forces of conquest for its own sake that the likes of Rajasthan and the Europeans have been kindly exporting to the rest of the world. Having rejected most European approaches but allowed a small number of Italians to trade in a few select ports, Japan has cherrypicked the best part of their world-view and decided to strike south to get its own slice of the colonies (albeit on an island where the Sulu themselves are also colonists). Another potential rival in the region?

Soon after, news arrive that those Italian traders have managed to strongarm one of the perpetually weak Chinese states into providing them with an exclusive treaty port. Seems like European colonialism is reaching all new theaters.

The Poles themselves are making good progress in Nowa Straya, where the local administration has requested and gained permission to form the first colonial Voivodeship outside Amatica. Based in the main port city of Eoragród (Sydney), the settlers have been happy to find that even if the outback wasteland seems to stretch on forever, the coast is nice, green and fertile and the hills chock full of precious metals. And it does mean some sort of victory over the Italians.

None of that translates into a real victory for Stanislaw II’s own policies, though, and he’s also not endearing himself to the nobles as he intervenes in matters that most rulers would either accept or at least overlook. Under his reign, all nobles’ foreign contacts will be strictly monitored and must go through official channels, even when they’re with nominally friendly or at least cordial nations. With three attempted coups funded by fellow Slavs against his predecessor Kazimierz II alone, he feels he has every reason to be paranoid of subjects and neighbors alike. He doesn’t hesitate to have them detained and punish them as harshly as he can without inciting a full-blown rebellion of his own.

Then again, he’s careful to try and maintain what friends he does have, and can’t allow any badmouthing of his wife Malfrida Artamonovich, cousin of the King of Chernigov. Sejmic deputies railing against her and her supposedly oversized role in the administration put not only the High King’s inner circle but also the alliance at risk.

The issue of Yugoslavia’s ragtag government is one that he believes is best solved by doubling down on it and expanding the client state to its intended borders rather than the husk it presently is. Thus, in February 1697, he decides to give his grumbling subjects something else to think about by invading Bosnia, the small South Slavic state part of the Francian Empire. As such, Navarra and its allies make the vain (and nominal) decision to try and protect it, but it should once again be a matter of just marching in and taking it.

Of course, he himself still needs to show his best side by leading the attack on the Bosnian capital, the rather humble town of Mostar.

As some empires expand, others are split apart: in this case the Inca Empire, the largest Native Alcadran state to quite successfully resist more than two centuries of European colonialism. Problem is, they chose to do so by stubbornly resisting anything that even distantly whiffed of European, including firearms and other purely practical inventions, which made them quite easy for Sweden and Asturias to brazenly slice up in the space of just a few years.

Meanwhile, even though Bosnia itself is quickly occupied, the Francians decide to pull the old stalling trick and refuse to sign an official peace before the High King personally puts a gun against the Emperor’s head (usually but not always figuratively). Though the Poles could just wait it out, Stanislaw II decides to take the bait and remind the enemy of their foolishness by indeed looting and occupying all their lands as well. This takes the Poles into their first direct confrontation with the Italians in a while: even though Italy itself isn’t in the war, it has allowed Navarra to hire one of its armies in true condottiero fashion. While Italian troops are certainly among the best Francia has to offer, the army is too small and tactically disadvantaged to pose a real threat to the Poles.

In late 1699, after a quick siege of Pamplona – a grand tradition that has frankly gone neglected for too long – it’s finally time to make a real effort towards ending this charade and truly assert long-lasting dominance over Europe. It’s a highly unusual demand, but as the Poles do in fact storm the Emperor’s residence and capture him alive, against all conventions of war and diplomacy the High King declares that he or his lands won’t be released until he makes a binding agreement (enforced by threats of Polish invasion, of course) to roll back several reforms of Francian government, most notably the Imperial Senate, which many would argue was just starting to recover from the chaos of the Heretics’ War over a century ago. Thing is, Poland would much prefer an internally divided, uncommunicative Francia, and now the Christians are indeed forced to return to the days of one-on-one diplomacy and ad hoc meetings. Well, on paper, anyway: in practice, Stanislaw II is certain that the Francians can get around the restrictions if they really want to, but this sort of upheaval is simply another slap in the face to add insult to injury and show how weak their elected leaders truly are. That should make them think twice before meddling in Polish wars again. The old man actually passes away some months later, only for the Electors to select his also elderly daughter as Empress, just as he’d hoped when he got the Senate to accept the possibility of one. Despite it being clear that there’s only one or two rulers possibly capable of handling the imperial appointment, they just keep on picking Navarra.

But now, Bosnia. It’s quite simply annexed whole and made just another administrative division in the Yugoslavian federation. The generals don’t even need to be told that Serbia is next.

As the 18th century comes to an end and the next one begins (in the Christian calendar, anyway), it’s becoming clearer and clearer that Stanislaw II’s “analytical” way of thought isn’t just an individual quirk, but part of a worldwide trend towards what could be generously described as “rationalism”. Though not inherently cold and uncaring, this philosophy emphasizes careful thought, observable fact and practical benefit over such matters as tradition, religion and emotion. Building on by now well-established staples such as empiricism (no relation to imperialism), rationalist thinkers encourage rulers to gauge and actually measure the effects of their policies rather than base them on simple belief. The most fervent rationalists exclaim that they are euphoric not because of any god’s blessing, but because they are enlightened by their intelligence. Indeed, “Enlightenment” is becoming one popular name for the phenomenon at large.

One founding center of the Enlightenment is found, surprisingly enough, in Kyoto. The Shogun has been thoroughly enraptured by the concept, or at least convinced of its practical merits, and put a lot of funding into his scholars’ efforts to collect, catalogue and hopefully analyze every bit of knowledge they can get their hands on. This also means sending out envoys to foreign lands, including Polish colonies in the East Indies and Nowa Straya. The Poles there are happy to provide some seemingly harmless scientific and everyday information, making sure to highlight the fact that they’re fellow pagans (the Japanese don’t seem to understand the concept) and thus natural allies against the hostile monotheists. However, Japan itself remains closed to foreign visitors.

The Shogun’s imperial ambitions are doing less stellar, though, as his war against the Sulu has stirred the Chinese into action and prompted a Yan-Wu combined invasion of Korea and Japan’s mainland holdings. Though the home islands remain untouched for the time being, Wu is in fact a major military power and more than strong enough to hold back the Japanese navy, stopping it from reclaiming the occupied provinces. In about a year’s time, the Japanese will indeed give up most of this territory and only be allowed to maintain a small strip of Korea, a humiliating blow dealt by people they’ve just loudly declared their lesser. The war against Sulu also ends up stalling and failing due to the delay.

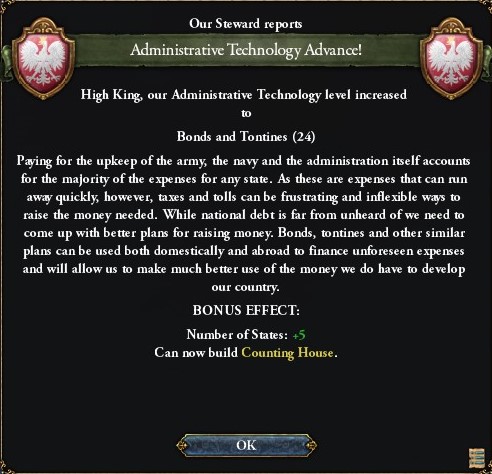

Stanislaw II himself does his best to keep up with these trends. A true Enlightenment state requires not only the will, but also the tools to keep track of the world, and thus the bureaucracy and economic bookkeeping always have to keep improving. Economic planning isn’t good for much if it can’t actually tell when more money is needed and then do something about it.

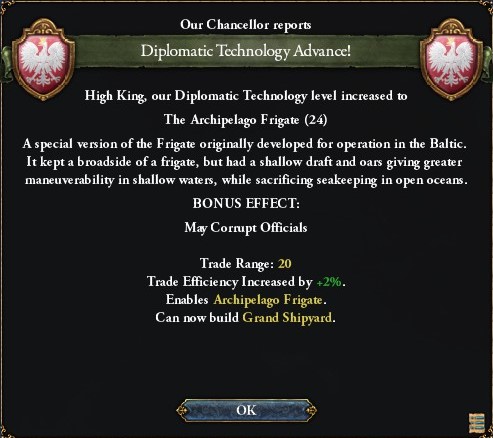

New feats of engineering also enable both advanced military designs and the facilities needed to construct them.

The High King is eager to start another war, but the Yugoslavian vassal government humbly requests – and rationally argues for – more time to integrate Bosnia, leading him to order the continued conquest of the East Indies instead. It seems that Poland’s expansion in the region has encouraged the local powers to seek external protection, though, forming alliances with each other, the Chinese and even faraway European powers. Christian naysayers have never posed an obstacle for Poland, of course, and the East India Company is urged to start an ambitious war that drags in Brunei, Sulu, Ligor and their so-called protector Asturias. The declaration is delivered to Burgos on Christmas Day 1701. Scotland is kind or opportunistic enough to join the Polish side.

Despite Stanislaw II’s confident demeanor and the seeming hopelessness of Asturias, though, this little colonial kerfuffle is slated to become a truly global conflict. Besides the scattered island outposts here and there, there’s plenty of border to be fought over in Amatica, and individual naval skirmishes and raids are already occurring all over the world along trade routes patrolled by both colonial empires. Whether the winner is inevitable or not, knowing the Francians, it’s going to be a long, painstaking process.

The Poles would rather keep it restricted to the colonies than wade through another guerrilla in Iberia, but that doesn’t mean the war won’t be devastating. All of Amatica does indeed become a massive battlefield as both sides’ colonial armies, eager for glory and conquest yet with little practical experience, go all in on the offensive while neglecting the defense of their own territory. When Stanislaw II hears of this, he has a rare fit of something resembling rage as he (very rationally, he’d like to add) recalls the Lukomorian Voivode, Szczesny Grzymala, to be tried for treason and criminal incompetence, ultimately leading to his beheading and replacement by the High King’s own candidate. Never before has a Voivode been dismissed by royal decree, never mind executed, and this causes a great stir within the (technically unlawful) colonial assemblies, disturbed by the fact that the High King is even able to do such a thing.

The one other Voivodeship doesn’t get off to a very good start either, as instead of focusing on the defense, Asturias manages to ship an army to Nowa Straya of all places. The small colonial militia wisely retreats into the wilderness, only to strike back after the main force has left the area, but reinforcements will be needed to take care of the threat, and the main force in the Indies already has its hands full.

As a side note, the seemingly rising star of Lorraine is violently shot down as disastrous wars against Germany and Cologne lead to it being thoroughly dismantled. Of course, its paths for the future were already quite limited, being squeezed in between Germany and Italy.

Once help finally does arrive, the Asturian army quickly finds itself stuck between an army and the merciless desert and is forced to surrender. In Amatica, on the other hand, even after the new Voivode succeeds in liberating Lukomoria, the fighting moves into the Appalachian Mountains, where the Slavic armies suffer several major defeats. Stanislaw II’s supposedly careful calculations seem to have forgotten about the Viceroyalty of the Zanaras, a deceptively wealthy colony with an army actually about as powerful as Scotland’s – not a problem for Poland itself, but more than enough to tip the scales in Amatica if Europe doesn’t intervene. Again, not once since the founding of the Voivodeships has the Crown Army been forced into action this side of the Atlantic, and the colonies are actually vehemently opposed to the idea, considering their militias a matter of great pride and “independence”. Too bad for them, they’re not in fact independent, and would do well to remember it. Stanislaw II starts preparing an army to take over the defense of Amatica.

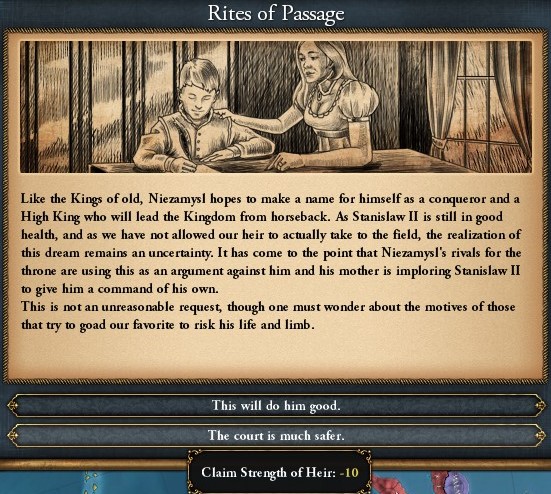

At the same time, though, he refuses any and all suggestions that his 20-year-old heir Niezamysl be allowed to lead an army in the field and prove his worth. The last thing he needs right now, as he finds himself surrounded by idiots, is either a dead heir or a rebellious one with an army behind him.

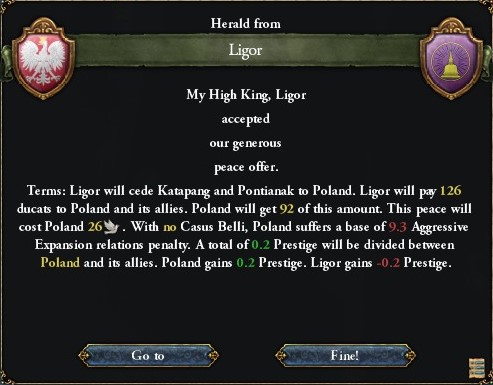

The first enemy to buckle is Ligor in July 1705, strengthening Poland’s hold on Borneo and leaving it with one less flea in its hair to worry about.

The army departs for Amatica onboard the Black Fleet, improvised for the purpose due to the most of the navy being busy elsewhere, but is caught out near Gibraltar while passing by Asturian territory. In the end, most of the fighting ships have to sacrifice themselves to allow even half of the transports to escape and continue west. Another great farce, though this one Stanislaw II has trouble blaming others for, as he was the one who ordered the Black Fleet – ill-suited for ocean warfare – to be used to begin with.

By the time the remaining reinforcements finally dock in Nowa Antwerpia and link up with the colonial armies, they’re only a blip on the map next to the massive but poorly led militia, albeit a blip led by Gen. Agafia Jastrzebiec, a product of Polish officer training. The colonials are less than happy about her being put in charge of the whole operation, but under her lead, they do start slowly but surely turning the situation around.

The war drags on. In Amatica and Asia alike the terrain is forbidding, distances long and supply lines lacking, making it even slower than it needs to be. At least the European theater remains blissfully quiet, with the Asturians eyeing an invasion of Frisia but wisely deciding against it and retreating. However, in late 1707, when the Frisian army decides to return the favor and scout out the Asturian positions, some malcontents at home take the opportunity to rise up in demand of a new republican government. Grand Duke van Breda is seen as a loyal lackey who either puts Polish interests before the Frisians' or is too busy kowtowing to pay attention, and the republicans believe that a locally elected government is the only thing capable of making Frisia anything but a Polish warhorse. Of course, the Polish troops stationed nearby quickly take care of the rebels, but they might be a worrying hint of things to come.

Gen. Jastrzebiec dies of a combat wound, leading to her speedy replacement by the even more capable Bozislava Dnistri who only lasts a couple years herself. Meanwhile in the Indies, troops under Gen. Drahoslava Ostrogski continue to trudge their way along the Bruneian-controlled Maharlika islands. (Philippines)

A timely large-scale rebellion of Andalusian settlers in Appalachia provides some much-appreciated distraction, but they also end up tangling with the Poles and only slowing down both sides for a while.

Whatever the Poles do, the Asturians are going to end up bleeding them anyway, and Stanislaw II’s efforts to rebuild the mangled navy are actually stopped by the sheer lack of serviceable sailors – and when he tries to enact some harsher conscription laws, they end up getting vetoed by the Sejm. Frustrated by the costly yet fruitless and potentially endless back-and-forth, yet unable to stomach what’d feel like a white peace with the Asturian bastards, in the spring of 1709 – 8 years into the war – he finally gears up for a direct invasion of the Asturian mainland that he wanted so much to avoid.

As Polish troops enter Asturias for yet another slow campaign through the mountains, far more important things might actually be happening right next door. Back in 1647, Italy’s full annexation of France briefly brought up the subject of trying to restore the Roman Empire, and in April 1710, that old speculation is fanned once more as the young and ambitious Queen Gizella I de Serra finally moves her capital from Pavia, where it’s been for over a thousand years, to Rome. She gives a long and dramatic speech about the shameful state that Francia once again finds itself in: falling apart at the seams, repeatedly invaded by Poland and recently even forced to abolish the Senate, the most important part of its government. She stops short of proclaiming any sort of “New Roman Empire”, but makes it clear through her borderline apocalyptic rhetoric just how vital it is that when the dullard in charge of Navarra dies, it is her that should be elected as Empress, and presumably her heirs after her. The elective system was necessary to shake off the Karling yoke for good (and bring on the rise of Italy), but in the centuries since then, it’s become nothing but the instrument of their own destruction.

And yet, if you ask the Electors, the valiant martyr Asturias is actually their favorite at the moment. And Sardinia is still voting for Navarra. The implications of Italy taking over the entire Empire if elected might not be the best campaign speech after all. Still, with the largest members growing and smaller ones disappearing while the imperial government itself withers on the vine, the Queen might have a point.

In one major break from Roman tradition, Gizella I takes the opportunity to declare another major reform: the banning of the slave trade within Italy and all its colonies. Santa Croce and Fiorita alike have been highly reliant on native and African slaves to work their plantations, but with slowing expansion and at the same time growing migration, new shipments of slaves have become less necessary, giving the Queen this chance to grandstand as some kind of historic liberator. Right now the ban only concerns the trade itself, but she hints at a gradual abolition of slavery altogether and economic sanctions against other states that refuse to comply.

Of course, many believe that this is just an underhanded move against Poland. Despite not using many slaves in its own colonies and having long since banned most forms of slavery in its European regions, Poland is in fact the second largest slave trader after Arabia thanks to its control of the West African coast, and abolitionism – should it spread much wider – would be a stinging blow against Slavs and Arabs alike. Stanislaw II, for what it’s worth, is less than interested in either bowing to the Italians or following their example just because.

Back to the war: with the invasion of Asturias, spearheaded by the High King in person, there’s finally some progress being made towards a favorable peace deal (the King would apparently be more than happy to let the fighting in the colonies continue from here to eternity). In the winter months, even Iberia gets its fair share of snow, and general and infantryman alike get to shiver and grumble (though the latter moreso). The actual fighting starts in earnest in December 1710, with nearly 100,000 soldiers on each side clashing in and around Burgos. Not least due to Stanislaw II’s own valor, the result is a series of great if not decisive victories for the Poles.

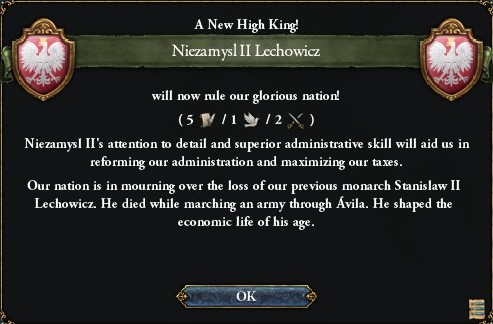

What is informally and somewhat derisively known as “Stanislaw II’s War” approaches its tenth anniversary, and just as the High King intuitively foretold, the guerrilla ends up being his personal undoing after all. Though he whips his army from victory to victory across Iberia, on 23 July 1711, a small detachment he is leading ends up getting separated from the main force thanks to a critical message being delivered to the wrong address, and by the time this is realized, they are already surrounded. As Christians crawl out from under every rock and tree stump, his men fight valiantly to the death, but as defeat seems inevitable, he recognizes that he is outmatched and seeks to parley. Accidentally or not – no one will ever be able to tell for sure – a cannonball explodes right next to him. His remains are only handed over to the Poles several months later… and in the meantime, his harsh and warlike legacy is passed on to the much more sheltered Niezamysl II, who still has an unpopular war to win.

The High King is dead! Long live High King Niezamysl II!

Spoiler: War & Map Highlights

- Germany has conquered not just southern Lorraine, but also most of Provence (previously under Tuscan rule) all the way down to the coast. Several colonial and native powers also took this opportunity to pick off Tuscan outposts around the world.

- England has finally managed to push Munster out of Cornwall and thus the island of Great Britain altogether, but Scotland remains a threat and Lancaster somehow still independent.

- Serbia won the war against Sardinia, acquiring its Greek-culture provinces.

Spoiler: CommentsI’m not screwing up on purpose just to nerf myself, alright? I’m just very bad at worldwide macro. Nice to see that it’s a sufficient handicap to keep me on my toes even while massively overpowered.

Nice to see that it’s a sufficient handicap to keep me on my toes even while massively overpowered.

Also: Unlike Vic 2, I’m not aware of EU4 giving Japan any special bonuses to westernization/catching up on tech. They just… did that anyway. Being the founder of any institution as a non-European nation feels like quite the feat, especially for the AI. On some level I’ve felt tired about Japan being the Asian powerhouse in most grand campaigns/alt-universe AARs I read, but I don’t think I mind it when it’s “deserved”. Well, not that they’re doing as well on the military side.Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-01-17 at 11:06 AM.

-

2020-01-17, 07:18 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Managing worldwide wars is indeed tough. I quit a France game because it was stressing me out more than I was enjoying it, honestly.

ithilanor on Steam.

-

2020-01-19, 09:05 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #42: When in Rome (Niezamysl II, 1711-1718)

Spoiler: Chapter23 July, 1711

Niezamysl II, 26 years old, has been relatively sheltered ever since his cloaking, as his predecessor was paranoid of him either dying, rebelling or being used against him should he be allowed to roam free or lead an army. However, if Stanislaw II could be seen as some sort of pseudo-rationalist, then Niezamysl II is a true Enlightenment prince in terms of his devotion to knowledge, science and the promotion thereof. Like any High King, he accepts the cruel realities of war, but doesn’t much appreciate them, and would rather end this struggle that has already claimed one ruler and several generals’ lives.

The population seems to agree. Even if war has not touched the mainland Polish population directly, they have certainly “noticed” the number of neighbors and siblings being shipped overseas to fight for some distant colonies that, sure, always sound very nice when the newspapers trumpet the Slavs’ latest conquests, but seem a lot less relevant when someone you know is sent off to die over them. There’s always been some fighting in the colonies, of course, but this has been the largest and longest by far.

The invasion of Iberia, though still promising, suffers some tactical defeats and setbacks which suggest that the war isn’t going to be over anytime soon if the High King doesn’t make it so. And indeed, on 24 December 1711, after precisely 10 years of war, a treaty is finally signed, seemingly bringing only petty border adjustments that leave much of the military unsatisfied but at least finally at peace.

The conquered areas are actually larger than, say, the two Grand Duchies of Pomerania and Lithuania combined, but the difference is that those are European and thus more important. And, to be fair, a lot more densely populated than Amatica. The East Indies do have a large (Sunni and Hindu) population, but Poland tends to treat the islands as a glorified plantation and trading post.

Indeed, despite being a victory in the end, the troubling turns of Stanislaw II’s War have brought up all kinds of new discourse in the Polish sphere: the slow response to the invasion of Nowa Straya. The pathetic performance of the Amatican armies. The arrest and execution of the Voivode of Lukomoria. The intervention of the Crown Army in the colonies’ internal matters. The horrible mishandling of the Black Fleet. The abortive republican uprising in Frisia. And last but still notable, the sheer non-involvement of Moldavia, which was ordered by Stanislaw II to stage a naval operation against Asturias but did literally zero fighting throughout the entire war, not even a single skirmish. The Moldavian Sejm brazenly argues that even if the High King is in charge of foreign policy and can declare war, what they actually do in it still up to them, no matter how clearly this flies against the spirit of the agreement. Especially as Moldavia doesn’t even contribute to the crown economy but in fact receives a number of subsidies, the literally centuries old grumbling about Moldavia exploiting Poland’s protection seems to reemerge, hearkening back to the days when it was still just a Grand Duchy.

Though the Polish colonial empire seems to be creaking a bit, its military should still be large enough to stop anyone from getting any funny ideas, though some doubt has been cast over its strategic competence. Military officials and crown liaisons in the colonies are not helping things by enacting extra taxes, tariffs and conscripts to make up for the resources spent defending them. Whatever the case, Niezamysl II is more than happy to let the situation cool down and refrain from any further conquests for the time being. Big wars like that really should be kept as a once-in-a-generation thing.

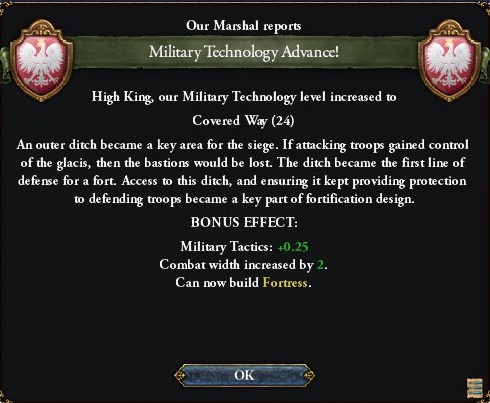

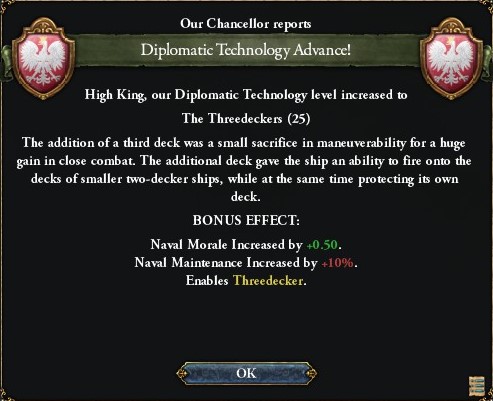

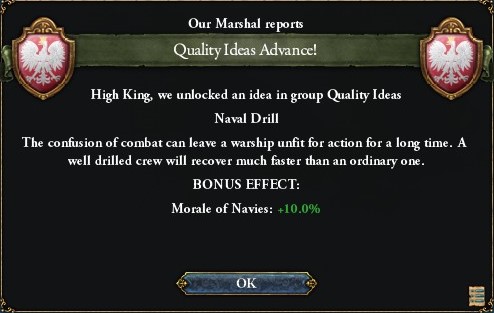

Some big readjustments are made to the military: a permanent presence will be established in Amatica and the East Indian garrison doubled, unpopular as this is with the locals and soldiers alike. New troops are recruited in Europe to make up the difference, including every available meczennik to ease the burden on the main population. Also, since a lot of the navy is being rebuilt or at least repaired anyway, it’s a good opportunity to update its heavy ship designs (to be even heavier, naturally).

There’s a whole new wave of less than enthusiastic sailors coming in, too, highlighting the importance of propel naval training and doctrine, both of which have received little attention until now. Seeing how good the navy is at just bumbling into a bad position and getting itself sunk immediately, there’s clearly a lot of work to be done in how they work together, both on a ship and a fleet-wide level.

The Queen of Italy has no qualms about exploiting this confusion, discreetly sending envoys and aid to malcontents in Poland’s colonial provinces in hopes that they’ll rebel and at least annoy the High King if nothing else. They seem to try a bit of missionary work on the side, too, but it isn’t too successful.

There should be no risk of Italy taking direct action, though, with the entire Mediterranean having suddenly erupted into a massive war of Rûm and Arabia against Sardinia, Italy and Navarra. Rûm’s main interest lies in Sardinian-controlled Rhodes, but depending on how the war goes, it could potentially lead to a lot bigger conquests in Africa or Greece for instance.

In Asia, another truly continent-wide war starts with Rajasthan and Karnata’s invasion of Wu and Yan. Rajasthan does have a reputation for punching way under its weight, but the balance still looks rather lopsided, and the Indians might end up finally shaking off their long stagnation.

Poland, for what it’s worth, remains nominally at peace. Amatica is in turmoil, though: besides having been thoroughly ravaged by the war, including a lot of fighting in the Jezioran countryside but also the densest parts of Lukomoria (even the capital Bakanów was stormed and occupied), you could say they’re less than happy with Krakow’s policies. They’ve proven perfectly capable of peace and coexistence with their Asturian neighbors, and all of a sudden they’re plunged into war for some land full of oddani they themselves don’t even want (or so they claim)? Many of them or their fathers left for the colonies exactly because they thought they’d get to be free of noble politics and needless war. And though their own armies were quite lackluster, what they saw of the Crown Army wasn’t very impressive either, and there’s a worrying idea brewing that with a little more drilling they could even take their independence by force. So they can go back to being peaceful, of course.

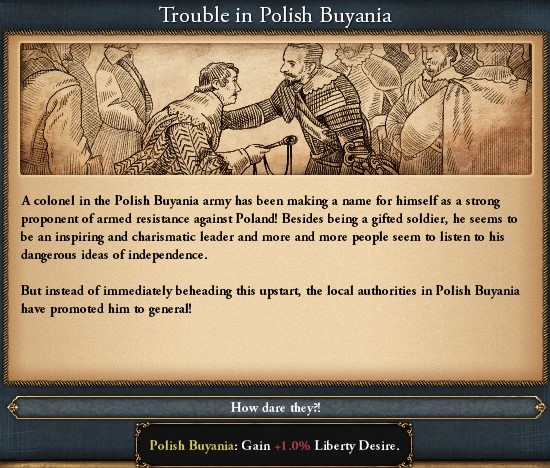

Buyania, the largest and most powerful of the three, is at the forefront of this movement despite taking the least damage in the war itself. Perhaps it hopes to dominate the other two after they break free. In 1715, Voivode Nadbor Kozelski – nearing the end of his first term and perhaps hoping to curry favor with his peers – starts getting more and more shameless, refusing to pay almost any tariffs and even openly supporting people actively agitating for independence. He only stops short of writing the declaration himself. Though hardliners in the Sejm demand that he be dismissed and brought to justice, Niezamysl II seems to favor appeasement and waiting the situation out. Others suspect that a delegation sent to arrest Kozelski very well might not return alive. His boldness does end up winning him a second term, allowing him to continue his provocations in hope of a third.

The High King may be a bit erudite and Bohemian (not literally) in nature, but he’s not a fool, and he can see that the situation is extremely delicate. As such, he decides to invest more time into his study of law and political philosophy, though some would argue that his approach is a bit too theoretical to be of much use.

As it happens, Niezamysl II isn’t Bohemian but actually half-Scottish. More specifically, his mother Anna was the third child of King Robert VI of Scotland, who bravely participated in Stanislaw II’s war. So when the first child disappeared under mysterious circumstances, the second died after only two years on the throne, and Anna herself is long dead of consumption, on 23 August 1716, Niezamysl II is informed that he may add “King of Scotland” to his impressive list of titles.

(Help me)

The Scots had first-row seats to witness the chaos of the last war, yet they somehow don’t think to veto this even when Niezamysl II hints that the option is available. They might be thinking that they, much like Moldavia, can simply use Poland as a cover and practically do what they want even while nominally subject to some distant High King. And in that, they’re probably right. Scotland lacks even a parliamentary system, which means that power is now placed in the hands of tiny circle of Edinburgh elites. In trade for their sovereignty, they get greater personal power than ever before, and precisely because the Polish empire has grown so large and complex, Niezamysl II has no choice but to give it to them. It is an interesting contrast with the independence-minded colonies, though.

Well, if they really do handle themselves, that’s fine. Poland is mostly focusing on economic and military reforms anyhow, and unlikely to be especially active in foreign politics for a good while longer.

After several years of fighting, the Mediterranean war ends in an awfully familiar-looking situation as Sardinia is simultaneously overrun by Rûm and Rûm by Italians, both sides deciding to call it a draw.

That leaves Italy with its hands free for what comes next. In early 1718, Germany declares war on Sardinia, in which Navarra intervenes but Italy doesn’t. In March, the 70-something Empress Blanca III finally croaks in her castle, but alas, Gizella I’s hopes are dashed as the Electors end up selecting the Navarran heir Jaime I after all, supposedly impressed by the previous Palafox’ devotion and worried by Italy’s open ambitions. This in spite of the fact that Jaime is a 19-year-old idiot wastrel (as described by Gizella) likely to either bring the whole Empire to ruin or, failing that, spend his reign living up in the mountains on imperial money. The Queen doesn’t much appreciate the fact that the title’s been in Navarra for most of the past century, while Italy, the clearly dominant power of the Empire, has barely gotten to taste it in almost three hundred years.

A few weeks after the Queen storms out of the electorate meeting in Pamplona (having been the only person to vote for herself), she makes a grand announcement: if the other Francians are too foolish to accept her as their ruler, she’ll just make her own Empire! Or more specifically, declare Italy the true and rightful heir of the Roman Empire, much like the Byzantines, Latins and arguably Francians before it. Though she’s reluctant to adopt the name of the Latin Empire, it having been such a total failure, the Italian Empire as she calls it does indeed control most of the ancient Roman heartland, and seems to have interest in the rest as well. As for her own title, it shall be Imperatrix Caesarissa Gissella Augusta – or just Empress or ‘Cesira’ for short. Apparently she was actually flirting with the idea of making Latin the official language, but alas, she doesn’t speak it very well herself.

And in case you missed it, yes, this means Italy is leaving Francia – entirely. None of its territory shall be considered part of the Empire, it shall not participate in imperial matters or the election, and the remaining Francians can probably look forward to what comes next. If there was ever a death blow dealt to Francia, this might be it, on 31 March 1718. What’s left of the Empire mostly consists of Asturias, Sardinia, and a divided gaggle of tiny principalities in increasingly perilous positions. It remains to be seen if Gizella and her successors can really fulfill her bold promises.

(Areas with lines over them are claimed by Francia but owned by non-Francians)

The Kingdom and now Empire of Italy is in many ways a very old-timey feudal nation with strong regional nobility stubbornly clinging to their traditional privileges, yet at the same time, it’s held together by a centralized, efficient and absolutist bureaucracy built around the Cesira herself. Its military is tactically, organizationally and technologically advanced – and almost as large as Poland’s – while the country’s central location has ensured that it remains a prosperous hotspot of trade and intellectual exchange. And as much as she uses Catholicism as a bludgeon to beat her rivals with, the charismatic and militarily minded Cesira isn’t so much a religious zealot as a dangerous opportunist.

Niezamysl II sure is happy to live in such interesting times.

Spoiler: War & Map HighlightsStanislaw II’s War (1701-1711)

Poland + Scotland vs. Brunei + Ligor + Sulu + Asturias

As usual, a war being named after the man who started it isn’t so much a mark of honor as shifting blame. What was expected to be a relatively easy tour of the East Indies ended up devolving into extended, bloody fighting in the wilderness of four continents and, while not necessarily the very first global war, certainly the first one the Poles care about. The Amatican, European and Pacific theaters were largely separate and each area’s own history remembers them differently, but after the back-and-forth in Amatica and the island hopping in the Pacific proved insufficient to make Asturias surrender, Stanislaw II was forced to begin the invasion of Iberia which he’d wanted to avoid, fittingly leading to his own death in the field and a swift peace by his successor Niezamysl II. Though the war itself was a victory, greatly expanding Poland’s colonies in both hemispheres, the aftermath and the events during it led to major reshuffling in the Polish military, as well as increased aspirations for independence in Amatica.

- It seems that after being denied its North Sea coastline, Germany really has been hard at work to strengthen the southern coastline no one knew it had.

- Andalusia is under attack by Kanem Bornu and Tripoli yet again.

- The notoriously rebellious Greeks have risen up once more, this time in Rûman-occupied Crete, and have had it on pretty strict lockdown for a while now.

The greater Lechowicz sphere in 1718. (Click to enlarge)

Spoiler: CommentsDo I look like a Habsburg to you!? I’m thinking that rather than force another breakup, if my PUs stay until Vic 2, I’ll just turn them into alliances and sphere of influence, which is basically how they’re acting anyway.

A shorter chapter, but I just felt like cutting it here and there were some overview things I was eager to get to. A bit of a breather before what I hope will be interesting days to come. There’s also another special coming up.

Much like Heretic Brexit, the whole thing with Italy is shamelessly modded on my part, but… well, so is the Francian Empire as a whole, and again I feel like it makes sense at this point from an in-universe perspective. Besides, no one else worries about me meddling with the events as much as I do. It was actually part of the coding that Italy wouldn’t leave if everyone else finally fell in line, elected it and then let it keep the throne, but for whatever reason everyone refuses to ever vote for it.Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-01-19 at 03:22 PM.

-

2020-01-23, 12:20 PM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2007

- Location

- Oxford, England

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Just dropping in to say I've been reading up on this since December, and am very interested to see it continue!

BTW, how far forward do the Paradox games extend? Is there a Cold War setting version? Can Poland into space-race?

-

2020-01-23, 02:06 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Good to have you!

Victoria 2 covers 1836-1936, and then Hearts of Iron 4 covers '36-'50. That's gonna be the end of the direct game-to-game conversion, I'm afraid, but if we ever get there I definitely plan to write an in-depth epilogue.

Poland can into space in the Paradox game Stellaris, but that starts in 2200 and runs on an interstellar scale, so it's more of a spiritual sequel with me having to fill in what happened in those 250 years. But again, should we get that far, I definitely want to at least experiment with it.

-

2020-01-24, 01:43 AM (ISO 8601)Barbarian in the Playground

- Join Date

- Dec 2009

- Location

- Massachusetts

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Just want to say I'm really happy this is still going!

-

2020-02-22, 09:50 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Special #6: Pagans of the World (1718)

Spoiler: OverviewAs the true essence of paganism lies not in the temples, festivals and fancy rituals but everyday life, natural locations, hunting and agriculture and so on, it’s to be expected that the increasingly urbanized upper classes would become somewhat detached from it. Still, the vast majority of the population lives much as they did hundreds of years ago, and their faith shows no sign of stagnating or fading. Even the rise of rationalism has done nothing to create any sort of “atheism”; maybe some deism and a few rare cases of misotheism, but even those aren’t widespread, merely philosophical thought experiments. Of course, denying the existence of the gods (or even any particular god) is among the gravest of crimes against Slavic Church dogma, which ties into its origins as a defense against Christian expansion.

In the general “pan-paganist” worldview, further refined by emerging Enlightenment intelligentsia, there was once some kind of original faith – based somewhere around the Black Sea – that all the present-day religions and their gods then split off from or reinterpreted. In light of this, polytheism reflects the natural state of things, any kind of paganism is more or less close enough, and any two religions can be somehow reconciled. Although, due to their location, the Slavs are obviously closest to the original. This also means that the Abrahamic faiths aren’t merely mistaken: their God (generally identified by Poles as “Jehowa”) is just as real as the others, but in fact a megalomaniac who betrayed every other deity by declaring himself the only one in existence and all the others false.

Thus the struggle between polytheism and monotheism, to those who take it seriously, is a kind of civil war against an evil usurper who would conquer the world and have every other god beheaded if given the chance. Firebrand speakers and even some theologians imagine that every holy war directly reflects the gods’ own battle on some other plane of existence. But, on the flipside, official policy is that since the oddani god is true as well, they can fit into society and even worship Jehowa just fine as long as they don’t cause trouble for the pagans. As if the oddani were ever in the position to oppress them. Besides, the idea that they’re worshipers of a traitor god as opposed to a false one might actually just be worse.

The Poles aren’t terribly interested in “saving” the traitor god’s worshipers, but they do want to protect the pagans of the world from falling under his thrall. Much of this, of course, is simple rhetoric to back up their own colonial ambitions, but most Slavs do believe in at least the basic concept of pan-paganism. On a world-wide scale, it might seem like the religious map is highly fragmented on all sides.

However, when you fudge the boundaries a bit to split the whole world cleanly into polytheists and monotheists…

(Black = Christianity, Judaism, Islam and Sikhism. White = everybody else.)

It’s only natural that the polytheists are winning, seeing as they obviously have more gods on their side. It’s also quite telling that, some local cults aside, the worshipers of Jehowa are really the only major monotheists around. This just further supports the idea that polytheism is the original faith and they the abomination. Luckily, even if Poland’s ideas of pagan unity are both hypocritical and vastly exaggerated, it’s definitely true that the various Jehowa-worshipers are far more dogmatic, ideologically divided, and prone to fighting over small differences in opinion, making it impossible for them to form a united front. Such is the influence of the traitor god.

The paganism of the Slavs and their neighbors has gotten a lot of attention, though, but the fate of their so-called brethren around the world much less so. As more and more of them fall under the influence of one foreign power or another, it’s worth taking a look at how they’re doing – while you still can.

Spoiler: AmaticaThe greatest success story of pan-paganism would have to be Polish Amatica. It’s pointless to try and describe the locals’ religious beliefs in a brief paragraph, since they’re just as diverse as you might expect from a continent covered in diverse cultures, but what matters to the Poles is that they’re pagans and worship a large number of gods and spirits. Only a few groups had (or at least used) writing before the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced to them, and they still seem to prefer oral tradition where possible, but Slavic scholars have devoted miles of paper to documenting them in their quest to prove how all pagans are actually related. The supposedly highest religious authority in the region is the Matriarch of Buyania, appointed really just to appease the clergy, but much like in Europe, the Slavic Church has made little effort to meddle in the locals’ actual beliefs.

Ever since harmonious first contact, armed conflict between Poles and Native Amaticans has been minimal, and they have been peacefully integrated instead. Of course, that’s glossing over the fact that the settlers have still barged into their lands, taken control of their resources, made themselves the de facto if not official ruling class, and forced countless tribes to choose between assimilation or relocation (often to the far reaches of the continent). Still, even if most of the treaties have been various levels of unequal and backed up by the looming threat of military force should all else fail, it’s certainly a better option than the even less diplomatic methods employed anywhere else.

The natives’ integration into Buyania, Lukomoria and Jeziora has been more so political than cultural or religious in nature. All three have effectively become patchwork federations of settler and tribal territories, each of which is represented in the colonial governments. While most tribes were semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers at the time of first contact, and some of them still choose to roam the vast Buyanian wilderness rather than settle down, a number of them already had highly developed farming civilizations. These were, and still are, especially common in the central region around the Great Lakes and the upstream Mississippi River, which the Poles once nicknamed ‘Little Europe’ for this very reason. In fact, some years after their arrival there was the illusion of all these tribes suddenly adopting European forms of government, but what actually happened was that they simply learned Polish and the Poles learned more about them, revealing just how similar they were from the start.

Large native town in the Jeziora riverlands.