Results 181 to 210 of 313

Thread: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

-

2020-06-16, 09:28 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-06-16 at 02:44 PM.

-

2020-06-16, 08:14 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- Earth and/or not-Earth

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

I also think that negotiating with the Amaticans is the best course. Moral and political issues aside, if Poland has to repeatedly suppress rebellions in its subject states it will soon reach a point where they're just not worth keeping around. It's better to give them some liberty and maintain economic ties than to either pour a never-ending flood of blood and treasure int suppressing revolts or losing and having them sever all ties with Poland.

I made a webcomic, featuring absurdity, terrible art, and alleged morals.

-

2020-07-08, 04:55 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #56: The Free Nations (1847-1848)

Spoiler: Chapter22nd of March, 1847

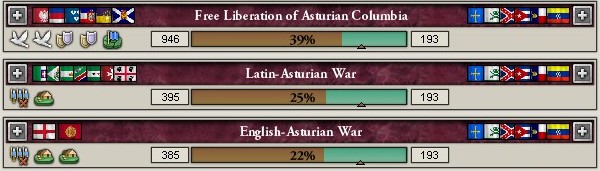

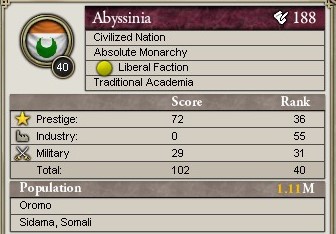

Only a few months into its term, the more moderate Sejm led by Mariusz Nowak is put to the test. The grueling oppression and occasionally flaring up brutality of Polish rule before, during and after the previous Amatican Revolution hasn’t been forgotten, and recently, the martyr Bozydar Radziwill’s famous Eagle’s Claw Speech has been more popular than ever. The blight of the Colonials has been likened to that of Poland’s various minorities and “Amatican” turned into a nationality of its own (muddling the fact that they’re actually European settlers in Native lands). But now, with the entire colonial empire being swept by waves of liberalism and nationalism, the three voivodes – actually installed in a series of coups to replace their Krakow-assigned predecessors – have once again come together to declare their independence with overwhelming popular support. The grandchildren of the revolutionaries from 71 years ago have risen up to take their revenge.

The news is received in the Sejm with a cacophony of shock, anger and resigned “told you so”. Though the Royalists, true to their name, seem to be aching for a repeat of the Royal-Colonial war, the other deputies are more clear-sighted. Another conflict against the voivodeships, even if they could morally stomach it, is a daunting prospect. Slowly ferrying armies back and forth across the Atlantic would be inconvenient at the best of times, and simply unimaginable when they’re urgently needed to maintain peace in Europe. The logistical issues would only be exacerbated by the fact that, in this age of citizen armies, the Colonials would have the home field advantage and plenty of patriots to draw from – plus their population has grown and they’ve learned from last time’s mistakes. For a number of reasons, the time when the Crown Army could simply land anywhere in the world and sweep through all resistance is long gone, even if not everyone realizes it. And so the Sejm tries to negotiate.

(This option leaves our influence at Cordial rather than outright Hostile)

Turns out that the Colonials realize all this too, and when they said “declaration”, they meant it. After the past century or so, they would put little faith in any Polish promises anyway. As far as Buyania, Lukomoria and Jeziora are concerned, they’re already independent, and it’s only out of common courtesy that they’re giving Poland the opportunity to pull out its armies before they’re thrown out or worse. The only “negotiation” to be had is for Poland to decide whether it wants to do this the easy way – or the hard way.

But even if a number of small colonies in Africa and Asia have declared independence just recently, those are different. The idea of a New World colony, settled and built from the ground up over several centuries, breaking free is unprecedented. How will the three voivodeships, each with fewer people and less industry than, say, Bohemia, protect their precious independence against foreign powers like Asturias? How do they expect their (intentionally) lopsided economies to function without the colonial network? And do they really expect their own alliance to last once they no longer have a common enemy, seeing how often they used to squabble even with Poland keeping them in line?

Their answer to all of these questions is the Free Nations of Amatica.

The three-person Trojka, representing the former voivodeships, serves as co-equal heads of state. The Congress is a bicameral legislature, one house having proportionate representation and the other two senators from each state to protect the more rural regions. Together with an independent judiciary, they form a loose federal system where every settler and native state is on near-equal terms with the central government. All in all, it seems almost a little too intricate to last, clearly just cobbled together in such a way that no one would have anything to complain about. Over in Europe, the Bundesrepublik’s federal experiment has proven less than stable, but the Amatican view seems to be that it only failed due to reactionary elements and foreign invasion, both of which the Free Nations are sure they can avoid.

To that end, they immediately commit to the most liberal programme they can think of: political, religious and economic freedoms, universal suffrage, easy paths to citizenship for any past and future immigrants – for they see immigration as the secret to their growth, and want to make this refuge from tyranny open to all comers. Buyania and Jeziora had already all but abolished slavery, despite not having had the legal authority to do so, and now that ban is extended to Lukomoria; the number of slaves in the Free Nations is negligible compared to most non-Polish colonies anyway, but the specific areas they (or rather their owners) are concentrated in won’t necessarily take this so well. The government must be aware that all of this will provoke the aforementioned “elements”, but they’re counting on their plans to create a land of true freedom and equality where those movements are choked out simply by leaving the people no reason to turn to such extreme methods.

And last but not least, the Free Nations select a new federal capital: Radawiec (Kingston), about as close to equal distance as you’re going to get from the regional capitals without trampling on Native territory, is rebranded as Radziwill to honor the posthumous prophet of the revolutionary cult. Ambitious renovations are planned to turn the small town into a booming hub, accommodate the new government, and celebrate the colonies’ history and independence.

Much of this already transpires while the first messages are still being passed between Europe and Amatica, but for lack of a better option, eventually the Sejm orders the troops to ship out, at least for the time being. Many have lived all or most of their lives in Amatica, and some of them choose to desert rather than move to Europe, but Poland has little ability to prosecute them. In return, the Free Nations allow Poland to maintain a diplomatic presence in Radziwill, but this is almost a trap of sorts, as the locals start calling it an “embassy” and thus an open recognition of independence. Were all this not happening across the ocean, a full month’s travel away, Poland certainly would’ve responded much more harshly, but geography has left it little choice.

The Royalists call for an immediate change of course or otherwise a new election, while the Populists are actually mostly alright with this. From their perspective, it’s been a long time since Amatica was a net positive for the country, an equal partner is better than a rebellious colony, and the Trojka has actually achieved much of what they themselves couldn’t. Stuck in between the two, the Coalition can only accept the situation; and since there’s little fear of the Royalists actually withdrawing their support for them and thus ceding even more power to the Populists, they feel relatively safe doing so. Of course, the Populists aren’t charity workers either: they believe that the Free Nations are packed with natural resources that colonial status has held them back from fully exploiting, and if their economy really does start to grow, Poland’s industrial magnates are looking forward to giving them the Lotharingian treatment.

Desperate, the Royalists turn to the High King for support, urging him to override or dismiss the Sejm, but he also has little will to go against the nobles or the cold, hard facts. The 57-year-old Nadbor III began his reign a long time ago vowing to defend Poland against the revolution, but after it actually became relevant, he hasn’t taken a very active role in the matter – and now he’s forced to try and defend this humiliating compromise with Amatican revolutionaries as better for Poland in the long run. The African and especially East Indian colonies are more important anyway, providing perhaps less manpower but far more wealth, exotic goods and vital naval bases. Besides, out of the “settler” colonies, the Voivodeship of Nowa Straya is still there – and has also seen a steady flow of migrants from Europe and Asia lately, drawn in by free land, liberty and mineral discoveries in the desert.

(Population grown by roughly 25% since 1836)

Of course, by focusing on the numbers, he’s dancing around the real issue: that the Free Nations’ fait accompli independence is a humiliation, a matter of principle, and the symbolism alone could in the worst case have a destructive ripple effect across the world.

To distract from this and bring his own message to the people, as well as symbolize Poland’s entry into a new era of prosperity, he announces a daring and innovative plan: since the controversial Miedzymorze railway is all but finished (despite the disruptions), he will ride a train from Lvov up to Gdansk (thus avoiding some of the more restless areas) and give a public speech at every stop along the way. On a greater scale than ever before, commoners across the country will have a chance to see and hear their beloved sovereign speak in person. He has good reason to believe that the monarchs have languished in their courts and palaces for too long, become too abstract, letting the people forget who they are and what they represent. Of course, he is aware of the risks on paper – but seemingly doesn’t think anything will really happen on this little adventure.

And indeed, it goes off without a hitch, though not without a bit of effort. The High King (with an unsubtle number of guards) boards a glistening black train that slowly, though still faster than any horse cart, huffs and puffs its way northward. Whenever it rolls into town, a spectacle of its own, he can always expect an enthusiastic reception from the crowd waiting for him to step out to the platform, dressed in somewhat less ostentatious regalia reminiscent of a fancy military uniform, and start talking. Of course, security is working overtime to keep any dangerous or just unseemly groups from approaching the site, but if there is any threat then they do a good job containing it, since it never makes itself known. The speeches are rather unoriginal in content, and blessedly short, but it seems he still holds onto some of the inspiring charisma of his younger days. To a critical listener, though, they seem to meander a bit as he emphasizes all the glory of Poland and its historical monarchy rather than actually address any of the things going on, apart from a few short and spiteful references to “anti-Polish” groups. In the end, the campaign can be considered a success in that no one died and the train didn’t break down, but an inconclusive one at best, as the High King returns to a Krakow and a political situation not much changed from when he left.

There isn’t much time to ponder the practical or philosophical implications of losing Amatica, though: while the revolutionary government over there tries to get itself sorted out, Poland is already distracted with something else. The King of Novgorod, elated with his recent victory over Chernigov, seems to be riding that high to assert dominance over his other traditional rival as well: Uralia. Besides its much-publicized (even if occasionally exaggerated) mistreatment of the Russian minority, the republic is obviously a large and noisy nuisance in Novgorod’s backyard. “Backyard” is a good description of Uralia in general, being so vast but mostly empty, and thus Novgorod is mostly interested in harnessing its natural resources for its own industry. Much like happened between Poland and Lotharingia, attempts to do this more peacefully have been met with resistance and government interference, so the King has decided to turn to force of arms. Nadbor III sees little reason not to continue to humor him, showing that he is either confident in Poland’s stability or again trying to draw attention away from it. Possibly both.

Uralia may not be a very appealing place to invade, but as it happens, it has – after first cutting ties with the Bundesrepublik – decided to make a defensive alliance with the new Germany just in case something like this happened. Of course, looking over from Poland, it would seem like they’re both overestimating Germany’s military readiness, but the Poles don’t mind getting an excuse to invade again. If anything, some think they might be doing the Germans a favor by stomping any potential rebels deeper into the ground while they’re there.

For Scotland, which doesn’t even have anything to do with the war, the timing couldn’t be worse. Some years ago, around the same time that Poland was struggling with a particularly bad case of potato blight, the same disease happened to strike Scottish-ruled Ireland infinitely worse. The adoption of the potato as a staple crop has fueled massive population growth, but at the cost of supplanting other crops and making Ireland entirely dependent on it. Thus, the explosive outbreak of 1845 threatened the whole island with starvation. Scotland, despite being highly reliant on its Irish provinces, still had a budget to balance in the wake of the war with England, and thus failed to commit as much aid there as it rightly should’ve. Hundreds of thousands have already died while others have fled to the colonies, but in between, the people who couldn’t or wouldn’t leave have grown enraged with Scottish rule. As this mixes with the general trend of liberal nationalism that Poland is all too familiar with, in the summer of 1847, Scotland suddenly finds itself facing an island-wide rebellion with seemingly half the populace marching out waving something, be it banners, guns, or pitchforks and clubs. And due to the war with Germany, Poland doesn’t really have any forces to divert there - if they could put down such a large uprising to begin with. The Irish Revolution of 1847 is truly the wrath of a nation scorned.

Poland certainly doesn’t want Scotland to shrink or the Isles to destabilize again, but there’s little it can do. In October, that’s exactly what happens, with the Irish Republic killing or pushing out the last of the Scottish troops, declaring its independence, and taking with it more than half the population of the entire kingdom. After centuries of relatively peaceful life as second-class citizens, the Irish seem eager to emphasize their own identity in any way possible, including a return to their Waldensian state religion and formalizing Irish Gaelic as its own language. England is happy to furnish them with money and grain shipments to deal with the ongoing famine, to be paid back at a later date of course. But, eventually the Irish will have to address the elephant in the room, the natural result of years of cohabitation: the considerable pagan, Yorkish, and pagan Yorkish minorities still in the country.

That being said, flashing back a bit: the Slavic alliance doesn’t have too much difficulty in its own war, with Germany getting invaded from several directions just like it was back in the Third Revolutionary War. Since there are so many troops moving through the area anyway, Poland also puts the finishing touches on its “soft takeover” of Bavaria, basically turning it into a stronghold against German reunification and an extension of Bohemian industry. Any resentment in the autocratic Bavarian government is balanced out by the fact that they share both of those priorities.

Aaaand as it happens, the Polish invasion is all it takes for the military to seize power in Frankfurt again. This time Ulrich Crantz has actually been sent away on an “extended vacation”, being deemed a clear liability based on his track record, and the government is formed by a junta of his former supporters in the Nationale Partei. The score sits at Nationals, 3 – Liberal Democrats, 2. The view of the ‘40s as one extended civil war for Germany gets even more evidence to back it up, not that it needed any.

Much to the High King’s consternation, Poland’s own unrest shows no signs of dying down, no matter how much he tries to will it out of existence. The fact that it’s still spreading in regions as different and distant as Bohemia and Crimea, or Denmark and Hungary, shows how pervasive the issues truly are. Mariusz Nowak’s Sejm does its best to stick to its more tolerant streak, but Nadbor III often seems to undermine them with his own words and deeds, intentionally or not. He certainly doesn't have as good personal rapport with Nowak as he did with Wladislaw Sarna.

All in all, it just isn’t enough. If Germany is caught in an extended civil war, then arguably so is Poland at this point, even if the leadership for whatever reason refuses to acknowledge it. The third major uprising within four years occurs in September 1847, inspired by the victories of Amatica and Ireland, government inaction on the promised reforms, and a healthy dose of opportunism given the ongoing war. It is now even more imperative that the war be finished and the troops brought home as soon as possible.

If the Poles had any deeper plans for Germany, they are quickly scrapped, and within a week the junta approaches them with an offer to hand over Germany’s remaining West African outposts (which it has no ability to govern anyway) in exchange for a separate peace. They're all too happy to accept, and turn their guns towards their own countrymen instead. Uralia too decides to fold once Germany is out of the game, accepting Novgorodian dominance over its economy and foreign policy, similar to the Lotharingian model.

With the war hastily wrapped up in only 4 months and troops on both fronts marching back towards Poland, the defeat of the insurrection is only a matter of time – though time it takes, continuing well into 1848 as the Crown Army clears out the major cities but then spends what feels like an eternity chasing down bands of stragglers in the countryside, where the rest of the inhabitants are a little too happy to give them shelter. But for all that military success, politically Poland’s crisis is deeper than ever. After the previous Sejm’s hardline policies provoked the revolutionaries, the Populists got a windfall of votes and Mariusz Nowak was propelled to power under the assumption and hope that they could find a compromise with the bloodthirsty peasants. A year after their election, that clearly hasn’t happened, and they’re being bombarded from both sides: the traditionalist side believes that their “weak” rhetoric and failure to crack down on the rebels have only made things even worse, while the liberals point out that no amount of empty words and shallow gestures will satisfy the crowds as long as their actual demands – namely the right to vote, right to organize and end to state censorship – are blocked by the majority in the Sejm and Crown Council alike.

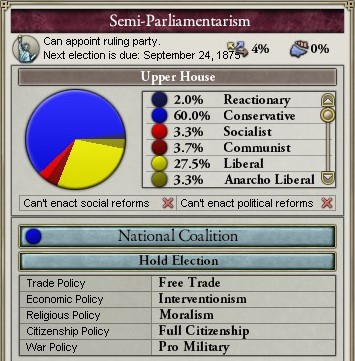

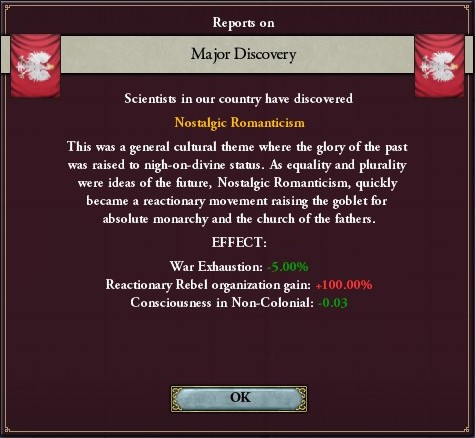

In 1848, the split between the upper and lower classes, the government and the people, seems to only be getting wider and less bridgeable. The government, simply unwilling to commit to the changes demanded, flips the other way and the seemingly suicidal hardline stance starts gaining more support once more. It's pushed along by some all too well written arguments from respected Polish thinkers.

(I forgot to remove the French Revolution references in these couple events, but oh well)

The revolutionaries, of course, can't help but notice this happening, and they too are faced with the same arbitrary choice: as the government has made it clear that it has no intent to act, they have exactly two options. Either they give up entirely, or accept that they’ll have to tear their rights out of the aristocrats’ cold dead hands or die trying. Liberty or Death. The stage is set for what might well become the worst period of the Polish Revolution, and the time that even the last doubters truly recognize it as one.

High King Nadbor III does not, in fact, have the legal right to force the Sejm to change its own rules, not that he'd necessarily do so even if he could. Though he too dreads the idea of a continuing, escalating revolution – even besides the part where he gets beheaded – in the end, as an elderly nobleman himself, it should come as no surprise that his sympathies lie with the nobility. He seems to have taken the people’s unwillingness to heed his magnificent speeches as a personal insult, and frankly can’t really see why these stupid changes are so important to them. Of course, he also has a rather reactionary Crown Council feeding those same talking points into his ear. As for Mariusz Nowak, his progressive programme has been totally discredited in record time, and thus the High King has him replaced with his personal favorite. However, while indeed a respected figure in most non-liberal circles, his pick Dariusz Zajkowski is an old aristocrat leaning heavily towards the reactionary end of the spectrum. Not only that, the fact that he’s gone out of his way to appoint a former general such as him seems like an ill omen of what is to come…

Spoiler: Meanwhile, Elsewhere[No new newspapers, actually. Hope that’s not a bug.]

Having stabilized itself and pushed aside the counter-revolutionaries, the Latin Federation is showing the world what an Italy not turned against itself is truly capable of. Shaping up to be a new Bundesrepublik indeed, it has rebuilt its army into one of the largest in the world, easily annexed Provence and then turned its eyes on Burgundy, eager to reclaim all the territory it considers a rightful part of Italy or France. Lotharingia, perhaps a little too cocky after its last victory against the far weaker Italian Empire, has come to Burgundy’s defense, which it might well come to regret. Poland is obviously too busy to intervene.

Spoiler: CommentsBarely one year, huh. But I figured that this was a good place to put a break, especially after such a text-heavy chapter.

The parliamentary mechanics, even when actually rather barebones, give me a lot more inspiration and tools for roleplaying internal politics than EU4 ever did. Of course, the world coming closer to the “current” day and “modernizing” in general also makes it easier to write walls of exposition about the political system, to me anyway. Does that make any sense?Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2022-03-22 at 12:46 PM.

-

2020-07-08, 08:13 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- Earth and/or not-Earth

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Things aren't looking too good for Poland. At least they don't have to deal with this revolt with half their armies in Amatica, though.

Also, it makes perfect sense to me that you'd be more familiar writing about governments that more closely resemble the one you live under.I made a webcomic, featuring absurdity, terrible art, and alleged morals.

-

2020-07-09, 02:22 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #57: The Long Revolution (1848-1850)

Spoiler: Chapter1st of June, 1848

Anyone struggling to understand the exact nature of the liberal revolution, either in retrospect or even at the time, is not alone. For all the slogans of “Freedom, Equality, Solidarity”, the unhelpful truth is that the liberal movement means something different for everyone. Some will go on to argue that the movement stems from “disgust at the ageless injustices present in a hierarchical society”, but few people really have the vision, ambition or energy to try and rip out the entire system with its roots, and certainly not a real alternative to take its place – yet – so instead they take it on piece by piece. While the movement is indeed popular with the lower classes as well, its leaders are mostly burghers, intellectuals or even minor gentry, and the closest thing it has to allies in the Sejm are rich people interested in freedom from regulations more than anything else. The only thing they all have in common is that they’re fighting for some particular sort of freedom they care about, be it concrete or abstract, big or small, positive or negative, and that even if they’d collapse into infighting immediately afterwards, they all believe their immediate goals would be met by replacing the government with a more democratic one. They’ll cross that bridge when they get there, but for now they must fight together.

Of course, no one turns to revolution as their first choice: it only reached this point after all levels of the Polish government, from local authorities up to the High King, staunchly refused any real attempts at reform and seemingly left violent upheaval as the only option. While the people don’t necessarily realize how divided the Sejm actually is on the matter, the results (or lack thereof) speak for themselves. Every act of reprisal by the Crown Army just further convinces the rebels that the system is rotten to the core. And while it is obvious that with sufficient violence, one side must break eventually, it’s less obvious who it will be – and how long this cycle of revenge would have to continue until then, if truly no compromise can be reached.

As for the groups most opposed to the liberal movement – for obviously the nobles would be powerless without at least some sort of support – one can name the clergy and professional soldiers, both of them rather useful in maintaining control of the country. While the movement can count some folk preachers among its ranks, the organized priesthood (pagan and oddani alike) finds the more religiously and socially liberal wing quite distasteful, and the Archpriest of Perun is an avowed pacifist urging an end to violence on both sides – which as we have seen only favors the status quo. The rebels and the military, meanwhile, share a mutual cultural, political and personal hatred of each other, only fanned the longer the conflict goes on and maintained by the soldiers living in a violent echo chamber where their entire career choice entails swearing obedience to the Crown.

And what of the nobles, the defendants in this trial? They have few arguments to present that would convince a modern audience, but while it’s hard to deny that they’re mostly driven by self-interest (as individuals or as a ruling class), they do have the power of tradition on their side: the monarchy, the church, the military, and all the good that Poland has done for its people, even bringing up its status as the “Savior of the Slavs”. Words like “mob rule” and “anarchy” also get thrown around a lot, Germany being the prime example. The constant fighting, whoever is really to blame, allows them to paint liberalism itself as a threat to Poland and any compromise as a moral defeat. And tradition shouldn’t be underestimated: for most people, the world isn’t really a changing place, nor do they want it to be, their lives defined by following in their parents’ footsteps and just doing as they did. Thus it would be misleading to claim that the lower classes are all united against their oppressors – many of them, the majority in fact, only want the chaos to end so they can go back to how things were. And of course, not nearly every liberal is a rebel either.

As of June 1848, the Crown Army has been fighting for almost a year straight, with a short lull in the spring soon interrupted by the latest uprising. The most stubborn pocket at the moment is concentrated in Bohemia (and neighboring Silesia), which despite being one of the oldest parts of Poland has always been a cultural crossroads of Slavic, German and Christian influence. Given its urban and cosmopolitan nature, it makes sense that it would remain a stronghold of liberalism. It deserves to be noted, though, that Czech nationalism has yet to become a major problem – they still identify as Polish citizens trying to transform their home country from within.

After appointing the former general Dariusz Zajkowski as Premier, High King Nadbor III has largely withdrawn from public matters and scurried off to a more secure location. Leadership, and responsibility for whatever happens, is thus left to the Sejm. Of course, the immediate policy wasn’t in doubt anyway: marching in and defeating the rebels by force, as many times as it takes. Them being a lot more concentrated and organized than ever before makes that harder, though, turning the whole summer into a bloody game of cat and mouse as Crown and rebel forces both try to avoid battles they can’t win and instead make one tactical retreat after another in search of better positions. As the rebels abandon their plans of capturing Prague itself, they consolidate to the south and east, moving worryingly close to Krakow.

Indeed, as the Crown forces close in on them, in September the rebels make a desperate push for the capital, left woefully under-defended in a critical oversight on Zajkowski’s part as he focused on offense above all else. Only by the rapid action of General Boleslaw Lechowicz is a defensive line put together, able to hold long enough for reinforcements to arrive, some of them actually taking advantage of the railway system for the first time to arrive inside the city and flank the rebels from there.

And so yet another “wave” of the rebellion is seemingly put down, but once again a large portion of the revolutionaries manages to evade capture, while more are already crawling out of the woodwork. Much as Zajkowski tries to sell it as a final, decisive victory – for the umpteenth time – people around him are aware that this battle still isn’t over, and the next one is probably only going to be bigger. Thus the military is kept on high alert, taking up positions around the country and patrolling the streets almost as if all of Poland were occupied enemy territory. In many places this police action and the response to it are harsh enough that not everyone believes the fighting has paused at all.

(That’s 242 regiments waiting to rise up – twice as large as our European army)

Meanwhile, as England is struggling with a general rebellion in its Welsh provinces in an ironic echo of its support for the Irish, Scotland decides to try and reclaim some prestige by starting a colonial war in West Africa. Poland is, of course, less than interested in helping at the moment. Angered by their ally’s inaction both now and during the Irish Rebellion, the Scots break off their old alliance with Poland – but just like happened the last time they threw a similar tantrum, they come crawling back only a few months later.

In Poland, the first months of 1849 are spent repeating an all too familiar pattern, with both sides clearly gearing up for another go, certainly not helping deescalate matters by publicly harassing and beating citizens accused of backing the enemy. In addition, until now, the war has been between the ragtag rebels and the Crown Army (with occasional Frisian or Yugoslavian support), but now there are signs of a real counter-revolution starting to form. Those not flocking to join the army are forming militias of their own, unofficial but enjoying Zajkowski’s vocal support and even access to stockpiles of old weaponry. Soon, violent clashes between "red" and "white" patrols become common sights in every major city across the country. Of course, ideological enemies are easily dismissed as just another reason to continue the fight, but eventually it dawns on the revolutionaries that many of these militias consist not of sworn reactionaries and monarchists but scared, angry and tired peasants grouping up to protect their community.

Indeed, there is the more important change: some 8 years after the very first clashes in Brest-Litovsk, it seems like popular opinion is finally turning against the revolutionaries. Growing opposition may mean little to true idealists, but waning support certainly does. Most of their goals haven’t lost any of their appeal, but the revolution as a method has. Even people sympathetic to them fear for their health and property – which are anyway synonymous for those dependent on their fields, animals and tools in order to live – and whether they blame the rebels or the Crown, the end result is that they want the fighting to stop. To the average person, life in Poland doesn’t seem actively terrible, while the previous years' fighting has lasted longer and been more intense than ever before. In regions that the rebels managed to “occupy” for a month or more, there was already enough time for infighting and chaotic incompetence to raise their heads and disillusion many of the inhabitants. Most of the revolutionaries are just regular people joining a cause they believe in, but now they’re being met with increasing peer pressure to give it up, not to mention pleas from their families not to get themselves killed.

Of course, that alone wouldn’t stop all of them, and the liberal ranks are too divided for any one leader to “decide to stop” either. Despite that, if a specific date had to be chosen for the end of the revolution, it would be 30 March 1849, when a young man, looking to be in his late 20’s, takes the stage in front of the thoroughly ransacked Cloth Hall in central Krakow. He introduces himself as Lech Lisowski, the leader of the Red Eagle Army. The nebulous group has always been a Crown obsession more than a liberal one, but even as it was conspicuously absent from the battlefield, the Crown’s dramatic rhetoric made it an enigmatic icon of the revolution for the general population as well, inspiring several copycat or “branch” groups to pop up. As word of Lisowski's public appearance spreads, a crowd quickly gathers around him. It is only by the guard captain’s better judgment that it doesn’t get violently dispersed, and he is allowed to speak.

Lech Lisowski explains how he and a group of fellow students at the University of Krakow first started the group in 1844 (when the liberal movement was already underway) with the best of intentions, out of anger at the Crown and the genuine need to do something. After their flags were discovered at the site of the Railway Rebellion, people on both sides latched onto them as a symbol. He cannot take credit for the revolution, but he feels all too much responsibility for his small part in what it has become. All those other friends have since died in the fighting, he explains, making their own choice to rush to the front lines while he stayed back and watched in terror. Echoing the feelings of the nation, with tears in his eyes, he says he never stopped believing in the revolution, yet it must end, and as he has been made into a symbol against his will, he can only try and act like one. Otherwise he fears that when the dust settles, years or decades in the future, there won’t be a Poland or a Polish people left.

He turns himself in, and by the High King’s unexpectedly wise intervention, his execution is commuted indefinitely, letting him be seen as a hero rather than a martyr. The same treatment is offered to any other rebel “leaders” who choose to give up now. That’s pushing it a little, of course: while a lot of prominent revolutionaries do fall off the map in the days and weeks that follow, most of them simply take their movements underground, pop up fighting in some other rebellion elsewhere or even just go back to their lives. But while it would be naïve to say that everyone simply sees the error in their ways and goes home, it is clear that the Long Revolution of 1841-1849 has reached an armistice if nothing else. That name is doubly appropriate, since it seems that if the revolutionaries are to achieve any of their goals, they will have to play the long game from here. But for now, Poland has stepped away from the brink of destruction – depending on who you believe – and it is time, to borrow an old cliché, to rebuild.

At first glance, it seems unlikely that the Sejm really learned its lesson in any way, having faced mounting resistance with more foolhardiness than courage and come out the other side without passing a single meaningful reform. If anything, at least right now, they feel more justified and vindicated than ever, and eager to return to business as usual.

Before this little distraction, they'd been dealing with the fallout of the loss of Amatica, and what they can do to stop that from happening elsewhere (or prepare for a future reconquest). Poland is only now looking into the “steamer” ships that are becoming more commonplace on the oceans of the world. Though largely untried in military use, being less dependent on the weather – even if it means burning coal instead – and more than twice as fast on long distances makes them a huge leap forward from traditional sailing ships, which haven’t really gotten much faster even as global empires continue to grow. Besides the peacetime benefits to trade and communication, they’d also let Poland respond to trouble in the colonies much more quickly. Private shipping companies have already been buying a few from abroad, but it’s about time that Poland jumpstarted its own production and began modernizing its merchant and military fleets. England and Scotland’s shipbuilding industries have gone all but bankrupt within the last few years, leaving Japan with a near-monopoly in a market that Poland is now looking to dip its toes into.

Poland also has a renewed interest in Africa, where it has generally kept only a minimum garrison. Out of the two armies that used to be stationed in Amatica, one will stay in Europe, but the other – together with the Atlantic Fleet – is rebased to Bissau, Senegal. Originally settled by Normandy in the 1600s, Senegal is one of the oldest and largest colonies in Africa, yet Poland has basically treated it as a glorified naval base and slave market (though due to a treaty signed with the locals, the slaves don’t come from the colony itself). With Asturias and England competing for the south, Sweden showing new interest in the Congo, and the Asian route around the continent becoming ever more important, Poland is not the only one starting to wonder how it could best exploit Africa. This also sparks new migration and investment in Senegal, including both military installations and the first (albeit modest) railway network south of the Sahara.

Meanwhile up north, the King of Sweden is forced to make a humiliating compromise with his rebellious subjects, turning Sweden into a constitutional monarchy where the once notoriously autocratic ruler struggles to hold onto what little influence he can. Much as happened with Italy, though, all his colonial subjects recognize the new government – but not without exploiting the power vacuum to grab a bit more autonomy for themselves. Yet at the same time, the liberal party, propelled to the top of the expanded Riksdag, starts preparing an array of reforms to alleviate the mistreatment of natives in the colonies. This is sure to cause no small amount of friction with the governors.

And at long last, after feelings have had some time to cool down and Zajkowski been mostly set aside by the Coalition once he'd served his purpose, the Sejm and Crown Council finally pass one of the Long Revolution’s three main demands; never mind that it’s arguably the least important one that least affects their own power. In January 1850, the Crown Censorship Bureau is officially shut down, abolishing systematic censorship of printing presses in Poland. Of course, it was never all that successful to begin with, but damn if it didn’t try, and harass or shut down a lot of publishers in the process. The bumbling bureau even played a key role in escalating the original Brest-Litovsk scandal, making it a symbolical target and convenient scapegoat for the government. Of course, the freedom of speech is still restricted by many laws, such as the bans on blasphemy, incitement to treason and lèse-majestè – as well as any kind of political organization – but assuming that the state doesn’t go entirely wild with its application of those, no longer is simply publishing something it doesn’t like considered a crime. Of course, it’ll take a while before the government gets over its old instincts, the situation will vary from time to time, and countless cases will be contested in court from here to eternity… but it’s still something.

The 1840s started off with the so-called Mad Year, but then more and more of those just kept coming, and in retrospect, the whole decade will be remembered as the Hungry ‘40s: hungry for change, hungry for liberty, in many places hungry for food. One can only pray that the ‘50s will be more pleasant.

Spoiler: Meanwhile, Elsewhere[Still no newspapers. Pretty sure it’s a bug, no idea what’s causing it, and no idea where to even look to solve it.]

The Latin invasion of Burgundy was aborted for reasons unknown, but to make up for it, the Federation annexed Lombardy instead and is currently marching into defenseless Brittany. Meanwhile, Germany is sneakily gobbling up what’s left of the Rhineland. Poland’s rivals have taken advantage of its awkward situation, and the Latins in particular enter the new decade perhaps more powerful than they’ve ever been. Scotland and England's jockeying for power, on the other hand, seems to have ended up with both of them weakened and humiliated by their own populace.

Spoiler: CommentsHalf this chapter is basically an attempt to try and explain both the massive escalation and the sudden end of the revolution. I was actually wondering if that last rebellion would pop and probably steamroll me, but RNG spared me on this day. Of course, I as the narrator would have the power to simply smooth over things in retrospect and act like it never got that bad to begin with, but that feels both boring and somehow… disingenuous? Not to mention writing myself into a corner every now and then between chapters.

I think I’ve mentioned before that rebellions in Paradox games are one of those things that both the game and the players tend to treat as much less impactful than they “should” be, if you consider how IRL uprisings and civil wars often become cultural touchstones for centuries to come. Worth noting, though, that out of the actual 1848 revolutions only a few actually had any lasting effect, even if they still went down in history.

Anyhow. The way that Vic 2 stops you from passing reforms until enough of the finicky upper house agrees to them can be a pain in a regular game, but for an AAR it seems to be an excellent way to get some tension without going out of your way to shoot yourself in the foot and delay the reform just because. But it also gets a little silly when they’re just too damn obstinate to pass a single tiny law even when faced with impending doom.

Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2022-03-22 at 01:49 PM.

-

2020-07-13, 05:00 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #58: World’s Unfair (1850-1852)

Spoiler: Chapter15th of January, 1850

A little less than a year after the unofficial end of the so-called Long Revolution, relations between the opposing factions have sufficiently thawed for the Sejm to pass its first major liberal reform and abolish the Crown Censorship Bureau, even over the protests of Premier Zajkowski. As previously shuttered printing presses reopen and new ones spring up like mushrooms, public discourse in Poland will soon become more vivid, diverse and colorful than ever, fighting a proxy war on the pages of newspapers even as political organizations remain outlawed. Of course, the liberal newspapers are balanced by a growing number of conservative, reactionary, loyalist, royalist, urban, rural, local, religious, and all kinds of other publications. That discourse will no doubt lead to continued demands for political action – but the people in power hope that opening this more peaceful outlet will at least placate them for the immediate future.

One long-standing international snarl is also resolved peacefully, when Sweden’s newly liberal government and the Alfmark governorship confirm the sale of the entire Tarnowski Bay (Hudson Bay) region to the Free Nations. Though land trades between nations are far from unprecedented, rather routine in fact, they usually concern much smaller border adjustments, not entire regions the size of Poland. Indeed, the only reason that this largest land trade in history is possible at all is because despite its size, the frozen wilderness has an absolutely negligible population. The Tarnowski Bay colony has been an unprofitable prestige project and source of needless tension since its inception, most obviously during the Amatican Revolutionary War when it was immediately occupied and a bunch of blood spilled for nothing (which, by the way, might well have happened again had the deal been refused). Sweden is all too happy to part with it in exchange for a hefty sum of money, free passage and fishing rights, and overall warmer relations with the Free Nations. Alfmark is freed from the burden of maintaining it, finally able to focus on its capital region. And while the inhabitants – coastal villagers, scattered woodsmen, and roving native bands – did not in fact receive a say in the matter, they’re mostly content with the Radziwill government’s promises of full civil rights and representation (and too few in number to cause much trouble if they tried). For their money, the Free Nations are left with uncontested control of the sea and basically all of northeast Amatica – a good trade for all.

From Poland’s point of view, this marks a serious recognition of the Free Nations as an independent country, and a major player at that. While few in the government maintain any real hopes of invading and restoring order to the Amatican provinces, the fact that it should be Sweden doing this seems to strike a nerve. While Poland narrowly averted a republican revolution, Sweden fell victim to the same, and the presence of a pagan constitutional monarchy just across the Baltic – or the land border from Scania – doesn’t sit well with a lot of people, digging up old grudges (such as Sweden’s support for the Bundesrepublik) and demand for some assertion of authority.

However, enthusiasm for needless military action – especially when Sweden remains allied to Chernigov, making any such war a two-front one – is quite low in the wake of Poland’s internal conflicts. Instead, a rather novel idea is suggested: as a demonstration of Polish prestige for domestic and international audiences alike, the country could host the very first World’s Fair, inviting all the great powers – and a slew of lesser ones, because why not – to put their artistic and technological splendor up for display. If successful, it could be a potent symbol of Polish influence and global goodwill, as well as a place to tie new treaties and trade deals.

Many dismiss the whole project as a frivolous pipe dream and a waste of time and money, especially when it comes to convincing rival and enemy nations to attend such a thing. However, it garners enough interest for a World’s Fair Committee to be tasked with seeing whether it could be done. Much to their surprise, the international reception is actually quite enthusiastic: even traditionally hostile countries like Germany and the Latin Federation, busy warring with their smaller neighbors no less, relish the opportunity for much the same reasons that the Poles do. After the upheaval of the Hungry ‘40s, the global hierarchy is in flux, and participation in such an event is seen as a mark of recognition (and a distraction) for relatively little investment. Once it is agreed that Poland will host the event, lesser nations actually start jockeying for the chance to send delegations as well. Construction of the appropriate venue, an international event in itself as every nation wants to build its own pavilion, begins immediately. The choice of location causes some debate in the Sejm, though, and in the end, Warsaw is chosen over Krakow in the name of national security and preserving the architectural sanctity of the ancient capital. Warsaw’s main competitors for the honor, Prague and Wroclaw, are both ultimately dismissed due to Bohemia and Silesia’s role in the Long Revolution and lingering concerns about any rebel presence there (though this aspect of the debate is kept under wraps).

Polish ships are heavily involved in moving all those participants and wares, providing a welcome boost for the related industries. Many of the enterprises formed in this period will go on to become mainstays in the field, not least HAPAG (Hamburg-Amatican Package Transport Inc.), founded by a Polish-German merchant family as one of the first devoted shipping lines to the independent Free Nations, thus a truly international company in many ways. Operating out of Hamburg at first but soon expanding to a number of Atlantic ports, it moves not just cargo and mail but also an unprecedented number of people as new steamer ships make the trip across the Atlantic a lot more palatable for emigrants, businessmen and diplomats alike. It is, of course, only a prime example of a wider trend: in the coming decades, similar companies will contribute to an exponential rise in emigration.

The Marynarka experiments with putting guns and thicker armor on commercial steamers. While it’ll take much more time for metal ships to outshine wooden ones in the Polish consciousness, the more forward-thinking parts of the navy are already proclaiming that frigates and galleons are a thing of the past and that while demolishing all of them is obviously unwise, no more should be built from now on, focusing entirely on steamers.

Meanwhile, having inadvertently put itself under a lot of pressure to appeal to the international audience, the Polish government finally passes a law with great symbolical but little practical effect (except for the people involved, anyway) that has been languishing at the bottom of the pile for a long time: the abolition of slavery. Most of Poland’s slaves and slave owners were in Amatica anyway, and as Sweden and England recently passed similar laws, leaving Asturias and Scotland as the only major slavers, what little demand there still was for them has also collapsed. Of course, enslavement through war has been illegal since the 1500s, but that just meant using African slave traders as intermediaries and not caring where they got their merchandise. This new legislation also leaves some major loopholes – not saying much about the other forms of forced labor used in the colonies – but still lets Poland boast of its credentials as a “civilized” nation.

Speaking of which, while Sweden managed to placate its colonies by leaving in even bigger loopholes and thus not actually changing much at all, in the case of England – already weakened by rebellion and war – demands for abolition have led to a major rift with the United Lordships, where as much as 38% of the population consists of Afro-Amatican slaves. Playing on both political and purely racist concerns, abolition was seen as not only an economic disaster but a threat to the very social fabric of the nation (which it certainly is, given that the nation is built on slavery) and a slippery slope towards the subjugation of the whites by a growing black population. As such, the colonial assembly (even the “liberal” majority) near-unanimously declared independence from England rather than give up their slaves, making the United Lordships the second former colony to accomplish such a feat.

What started out as a bureaucratic grouping of smaller colonies has thus become another federal nation, albeit with only 3 ½ states in contrast to the Free Nations’ 23 states and 7 territories. The eponymous Lordships – Elysia, Arcadia and Sudenia – form a confusing, staggeringly anachronistic, almost neo-feudal system with each of them ruled by a hereditary Lord, but also a National Diet elected by everyone above a certain wealth level and a House of Peers consisting of the country’s richest and most powerful. Fiorita, far to the south, is a federal demesne, as is the newly established Camelot City (Washington D.C.), which serves as the capital and neutral meeting ground. All in all, this bizarre political experiment and positively Arthurian aesthetic seem designed to preserve a supremacy of traditional values and, chief among them, the continuation of slavery. Their stated ideals are in many ways the polar opposite of the much, much larger Free Nations looming ominously over them.

Some months pass. England, with no hope of reclaiming the Lordships, invades Wales instead, anxious to reannex the country before it can build a proper army or secure too much international recognition (preferably before the World's Fair). Scotland, apparently inspired by this, wants to do the same with Ireland, not least because it actually has the capacity to become a real rival in the future if not taken out in its infancy.

Problem is, Ireland has already secured a powerful sponsor: the Latin Federation, whose conservative government is running on a platform of Christian unity. As they’re wont do, the Scots only inform the Poles of the declaration of war after it’s already been sent, putting them in quite a bind. On one hand, Poland obviously supports Scotland’s claim to the island, and wouldn’t mind seeing it reclaimed. On the other hand, over time it has become less and less useful as an ally and more of a liability, and there’s serious talk of simply abandoning the on-and-off alliance for good. On the other other hand, Scottish defeat in this war could well lead to a total collapse of pagan power in the British Isles, which have once again become a highly symbolical battleground for bitter religious warfare. But most importantly, Poland joining in the fight would mean pitting the two most powerful great powers against each other for the first time since the Treaty of Rome in 1738. History has deemed that originally controversial peace treaty vastly beneficial for both sides – are they really going to abandon it over something like this?

In July 1850, as has been done with similar decisions in the past, Nadbor III brings the question to the Sejm, where opinions over the complex matter are split even within factions. The Populists are almost uniformly opposed, being relatively uninterested in military adventures, afraid of the damage to diplomacy and trade all across Europe, quietly sympathetic to the Irish, and perhaps just a little bit spiteful. The Coalition, in true moderate tradition, is split almost perfectly in half. And even the Royalists, surprisingly enough, can’t entirely decide between aggressive jingoism and isolationist “slavocentrism”.

Premier Zajkowski, relegated to the back bench as the Sejm focused on more civil and peaceful matters for a while, sees his moment to shine. Besides being famously zealous, merciless and undiplomatic, he has a personal fondness for the Scots, having fought there alongside them during the Third Revolutionary War. He angrily admonishes those nitpicking the difference between Slavic and Nordic pagans, reminding them that the Scots are brave, loyal (?) friends of Poland who he knows from experience would surely come to their aid if the roles were reversed (thankfully he doesn’t launch into another of his rambling war stories). What message would it send to the world if Poland were to sit on its hands and abandon its allies in the face of the Christian menace? Clichés and platitudes aside, his passionate appeal helps shift the discussion from the practical details to matters of principle, making him feel like a true Premier and not just an old warhorse for perhaps the first time.

Rounded out by a few promises and political appointments behind the scenes, Zajkowski manages to secure a narrow majority in favor of war. Much like England’s invasion of Scotland brought about a historic clash between the great powers, Scotland’s invasion of Ireland is about to cause a possibly even bigger one. And as this one also involves Poland facing against a revolutionary republic, people can only wonder if it’ll end up earning the title of Fourth Revolutionary War.

As is often the case, on paper the Polish alliance seems to have an advantage in numbers, but in reality the location of those troops is equally important. Poland and the Latin Federation are both global empires, and while the Latins’ situation is unclear, what is known is that a fifth of Poland’s land forces are stationed overseas, and even the ones in Europe are scattered across the country, many of them slated to take as long as five months just to reach the front (and leave the rest of the country undefended). The growing railway network makes this somewhat more bearable than it used to be, but technical problems and limited capacity mean that the issue remains. However, the good news (for defense) is that Germany is unlikely to allow passage for either side, as is Lotharingia, reducing the land border between the two to just Calais and nothing else. That leaves a naval invasion, most likely into Yugoslavia, as the other thing to worry about. Of course, on the offense, these difficulties apply for Poland in equal measure.

In terms of realistic options, the most preferable would be a rapid occupation of Ireland (which doesn’t have much of an army of its own) and something of a fait accompli victory, and to that end, a fleet of steamer transports sets off from Denmark while the Grand Marynarka takes control of the English Channel. However, the Latins seem unlikely to accept defeat that easily, so some invasion of their homeland might still turn out to be necessary.

At least the Italian colonies in West Africa and the Maniolas prove very lightly defended, making it easy for the Polish garrisons there to occupy them in just a few months, but this raises the concern that all those missing troops might be in Europe instead.

As maneuvering ramps up, both the Crown Army and the Marynarka give off the impression of being in very good shape after years of high recruitment, funding and overall attention.

But speaking of attention, in all this blustering for war, something else is quite totally forgotten: the World’s Fair. No one in the government has any time, effort or funding to spare for that parade of idealistic posturing, and those who even remember it exists mostly seem to laugh at it. The sudden outbreak of war actually causes a bit of a scuffle in Warsaw, as Polish forces try to arrest the Latin delegation and confiscate their goods; after a few days of tense negotiations, they’re allowed to leave with most of their things intact, but the incident causes many neutral parties to pull out of the event as well, be it due to outrage or just seeing the writing on the wall. Due to the sudden disappearance of both domestic and international support, the whole thing is doomed, much to the chagrin of its prime architects who’d gotten quite emotionally invested in it. In the end, the only countries that don’t pull out are Poland, Scotland and a somewhat confused Karnata. Needless to say, the so-called World’s Fair ends up being a farcical showcase of Polish-Scottish propaganda and not much else, which no one involved will soon forget – no matter how they wish they could. Some of the displays already built are left behind as an embarrassing reminder, to be later repurposed as galleries, gazebos or even just storage.

Internationally, the World’s Fair is even overshadowed by the German military junta’s declaration of war upon the “rebel province” of Switzerland. This also pulls in Lotharingia to Switzerland’s defense, meaning that there’s now a separate smaller war going on in Central Europe, surrounded on all sides by the Polish-Latin one.

Well, not that there’s much fighting going on. Polish and Scottish forces are marching across Ireland, but in Calais and the Adriatic the first seven months of the war are mostly a tense standoff (and a few naval skirmishes with minor losses), both sides waiting for the other to abandon their fortified positions and make the first move. At least this gives the troops ample time to move to the front. However, if no one does anything, the war might drag on for gods know who long, terrifying the more economically-minded parts of the government.

That breakthrough is finally made in February 1851 when amassed artillery blows a hole in the Latin defensive line, allowing Polish and Frisian forces to flood into northern France. However, that’s when the Latin army springs into action as well, starting to bring in its reserves – including tens of thousands of citizen soldiers – in an attempt to overwhelm the Polish forces and cut off their supply lines. Apparently threatened with invasion (and not a friend of Poland anyway), Lotharingia also chooses this time to break its neutral policy, allowing Latin troops military access and thus widening the front dozenfold. Poland angrily demands and receives the same, but this is by no means a welcome development right now.

At first, the situation remains broadly under control: Latin leadership on both the tactical and strategic levels leaves a lot to be desired, leading Polish analysts to suggest that the post-revolution purge in the Federation also ended up targeting a lot of the officer corps. Paris falls in May – a traditional milestone in any western war, if rarely a decisive one – and as usual, the new focus is on keeping it. However, it seems that even if the Poles can reliably win any battle they get to pick, there’s just so many Latin conscripts running around that whenever they're winning in one place, they’re almost inevitably getting caught out in another.

On another front, as the same old King of Novgorod has gotten even more full of himself and ended up breaking his alliance with Poland, he is left open to Chernihiv payback as the other kingdom declares its intent to reclaim the territory it lost only nine years ago. Moldavia stands by Novgorod, as per usual, but Chernigov has both Sweden and the similarly revanchist Madjid Caliphate on its side (as well as the Shan Empire, because why not), making this a gigantic land war stretching from the Arctic Sea to the Indian Ocean. Whatever happens, it seems that Novgorod’s brief time in the spotlight, achieved by ruthless aggression against its neighbors, is about to come to a brutal end. So much for the peaceful ‘50s indeed.

Ultimately, the Latin counteroffensive is sufficiently strong and constant that by August, the Crown Army decides it has no choice but to retreat back to its now much longer defensive line, i.e. square one. By October, basically all the progress in France has been undone. While a sound strategic decision, at home, this is seen a great humiliation for both the Crown Army and the armchair generals in the Sejm, not least Premier Zajkowski himself.

Out of sheer frustration, and as they actually have an election awaiting them in just a few months, the Poles (and their puppets alongside them) have no choice but to launch a fierce counterattack, no matter the cost in lives. The good news is, whatever the situation on the continent, they have Ireland sufficiently locked down that it has no choice but to accept reintegration at gunpoint (several of its defiant leaders already executed for their crimes in the revolution). Few really believe that the matter has been settled with this, obviously, but it has been pushed back underground by force of arms.

(No screenshot, apparently, but Ireland was fully annexed.)

The problem then remains whether the Latins will simply accept this, or keep fighting to liberate their Irish brothers in the faith. As it turns out, they and their voters have made a quick turnabout and decided that Irish independence (they’re not even Catholic!) isn’t worth making France into a battlefield for another several years, especially as there’s little hope of getting an army past the Marynarka and Poland’s failed offensives give a taste of what any attack into Frisia would probably look like as well. That leaves the ball in Poland’s court: peace out, or push for some of the Latin colonies it has occupied?

The goal of the war has already been accomplished, and the Coalition is anxious to get it over with. Their massive trouncing in the last election has led them to assume that stretched out hostilities aren’t necessarily good for them when it comes to getting votes. And so, on 20 November 1851, Poland and the Latin Federation agree to cease hostilities and recognize Scottish de facto rule in Ireland. Outcome: a return to the status quo of 1847. Casualties: a lot of good men and women, and the stillborn World’s Fair.

In the end, to everyone’s great relief, the 17-month war didn’t really deserve the Fourth Revolutionary title, being remembered as the (end of the) Irish Revolutionary War instead. What it did was highlight some new military realities that the Poles will have to digest: that geography, tactical developments and the strength of the Latin army make land wars an increasingly imprudent way to conduct diplomacy, even before getting into the economic and highly contentious political side of it. On the other hand, the end of the war is seen by some as a sign that the great powers, even across the religious and ideological divide, can come to the negotiating table and coldly decide the fates of lesser nations when they decide that is more convenient for them.

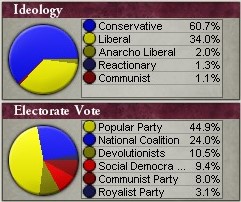

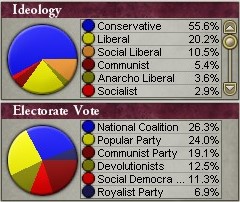

There is considerable anxiety over what the first election since the end of the Long Revolution will look like. But as the debates and campaigns start picking up speed in early 1852, preparing for the late June election day, they seem to go rather smoothly, with only a few hiccups such as the Populists having to be given a firm reminder that any campaigning aimed at people not actually allowed to vote will be seen as rabble-rousing if not treason.

However, even if not violent, it’s clear from the start that the election will be an extremely close one, and in stark contrast to 1845 (when sheer complacency played a major role in the Coalition losing its dominance for the first time) every party acts like the election is theirs to win or lose. But precisely because the election only involves the upper classes, they’re able to avoid the most sensitive subjects of the last decade and focus on more topical ones instead, such as foreign and military policy. These questions also have a clear split among factional lines, but are not quite so obviously liberal vs. reactionary as to be directly associated with Poland’s internal conflicts. On matters that are, such as civil rights and religion, almost all debaters are careful not to rock the boat. The general public and the uncensored press are watching more closely than ever, reporting and commenting on their every move.

As the results start coming in, both the Coalition and the Populists soon start to claim victory by their own definitions. The Royalists are indisputably the losers here, having won only a few individual districts and given many vindicated conservatives a chance to snark that they can only get votes by appealing to people’s base instincts in a time of crisis. However, the popular vote (of the 2% allowed to participate) is where it gets dicey: it shows that the Popular Party "should" have won by a large margin were the Sejm based on proportional representation like any modern parliament, yet thanks to the way the voting districts happen to be laid out, the Coalition instead regains a full (if narrow) majority in the Sejm. In particular, the Populists note, they won a blow-out victory in almost all the largest cities and only lost by the narrowest of margins in others. It’s the first time that the electoral system has produced such a blatantly unfair outcome – warping not just the number of seats but even the overall winner – which brings it under fire from the Populists but also the Royalists, who feel they should've had ten times as many seats as they actually got. The fact that these things are being discussed in such stark terms is the final proof that party organization and identity have found their home in Polish politics, too – how else would all three parties be pulling up exact percentages of how much “their candidates” won?

The Coalition can hardly deny that its victory looks undeserved if that’s the way you choose to look at it, but counters that the system is only doing what it's meant to do and ensuring fair representation for all parts of the kingdom, rather than letting the disproportionately liberal cities dominate over the countryside. Of course, this just confirms to all in and outside the party that the system is in the Coalition’s favor and they have absolutely no motivation to change it.

But with a majority comes great responsibility: since 1846, the Coalition has been forced to work with either the Populists or the Royalists to get anything done, thus also allowing it deflect blame onto them for any missteps or compromises (such as Amatica or the suspiciously liberal-tainted reforms passed in the last couple years). For this upcoming term, as long as it can keep its own members together, the Coalition can do or not do anything entirely at its own leisure, but that also means answering for it – both to the voters and the increasingly critical rest of the population. It’s already been shown that unwillingness to pass any liberal reforms whatsoever can lead to disaster – but can the Coalition compromise with itself?

Spoiler: Meanwhile, ElsewhereNewspaper Gallery

[Only one, but at least it turns out they are working!]

Unsurprisingly, England succeeded in reconquering Wales. Germany’s war was quite a bit longer and harder-fought, but successful nonetheless. As the unrest in Germany seems to be over at last, with the aggressively nationalist military government consolidating its power, Lotharingia has made a rather desperate alliance with both Burgundy and Bavaria and might also have to be more receptive to Polish diplomacy in the future.

Novgorod seems to have made some admirable progress into both Sweden and Chernigov at first, only to lose the initiative and be put firmly on the defensive (and not a very good one) since then. It’s hard to imagine the war here lasting very long.

Moldavia, on the other hand, is showing once more that it deserves its seat among the great powers, turning around Chernihiv-Arabian hopes of flanking it by successfully invading both of them at the same time. It has few options when it comes to directly saving Novgorod, though.

Unsurprisingly, China has fallen into an extremely messy struggle for dominance, with especially the Pratihara breakaway kingdoms invading and being invaded by each other in turn. Although, some observers say that it might end up being the stable and modern-ish Republic of Manchuria that reaps the greatest rewards from this chaos.

Spoiler: CommentsI only now realized that I accidentally changed the name of the Royal Faction to Royalist Party at some point. It wasn’t intentional, but pretty appropriate, I suppose.

I expected this to be a bit of a breather chapter, shedding some interesting light on the world of international politics. Which I guess it did, just not the way I thought.

The 1800s were in many ways an era of great power conferences and treaties, which Vic 2 also plays with, but in this timeline they’ve obviously been a lot more violent and tumultuous so far, so I felt the need to lay some narrative groundwork for more amicable diplomacy in the future. But that doesn’t preclude the option of that diplomacy failing horribly, of course.

I keep bringing up the concept of “citizen soldiers” a lot, not really an established or mainstream term IRL but I think convenient in the context of this AAR. Any country can mobilize its population, and democracies aren’t even better at it or anything, but besides me finding it a hassle gameplay-wise, it is also true that it comes with notable downsides, downsides which combined with the unrest caused by a long and severe war can be a lot more significant for a more autocratic country with an unhappy population. Besides, drafting your citizens in a hurry and sending them off to the front wasn’t really the norm in this period like it became in the World Wars, so it makes sense to me to dress it as a republican peculiarity, especially as it was notably pioneered during the French Revolution – and to make them a bit more threatening in-universe.

Side note: In the preparation for this game, I added an event where the overlord country banning slavery triggers a choice in all of their colonial puppets, letting them either follow suit, or keep their slaves and declare independence (giving the overlord a casus belli). The event is coded so that if the country doesn’t have any slaves, like the Swedish colonies due to a technicality, they’ll always accept; meanwhile, the higher the support for slavery, the larger the chance of rebellion, as happened in the United Lordships. Whether a breakaway colony becomes a democracy or a constitutional monarchy is also random, heavily weighed towards democracy but also affected by reactionary ideology in the government and population.

The phrase of the week is fait accompli.Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2022-03-22 at 02:25 PM.

-

2020-07-13, 04:53 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- Feb 2016

- Location

- Earth and/or not-Earth

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

A reasonable showing by the Polish army, though they're unlikely to be dictating peace at the gates of Rome again any time soon.

And based on those election results, it looks like there's a good amount of gerrymandering going on as well.I made a webcomic, featuring absurdity, terrible art, and alleged morals.

-

2020-07-13, 05:13 PM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

I don't really picture it as a matter of gerrymandering (yet, anyway), as the electoral districts are for now based on traditional town and county limits and whatnot (though those can obviously be pretty funky in their own unintentional ways). It's just that in a first-past-the-post system, a blowout victory in any given district brings you no benefit over a narrow one while a narrow defeat is as good as nothing, disadvantaging the liberals whose voters tend to be more concentrated than the conservatives'.

Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-07-13 at 05:14 PM.

-

2020-07-13, 05:34 PM (ISO 8601)Ogre in the Playground

- Join Date

- May 2009

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

InvisibleBison: As SilverLeaf said, it's more likely to be things like rotten boroughs, though gerrymandering's definitely possible.

This is definitely a bit more violent than either the historical period or your average Vic2 game (at least in my experience). I think I remember you mentioning that cores are a bit more widespread than they are in vanilla Vic2, which would account for the increased wars; the lack of good CBs is the main thing keeping intra-European wars in vanilla under control.ithilanor on Steam.

-

2020-07-14, 05:43 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Yeah, that's true. Come to think of it, I think almost every major war in Europe so far has been over cores, be it longstanding border conflicts (York, Franche-Comté, Smolensk) or reclaiming rebel provinces (most of the German and Latin wars, Ireland). The wars in China, meanwhile, are both pretty appropriate (good old Chinese civil wars) and based on either the Reunify China CB or Japan just nabbing some colonies. I wonder if China's actually going to be reunified at any point. While that would be cool, having it become two or three "big but not ridiculous" countries would be nice too.

Last edited by SilverLeaf167; 2020-07-14 at 06:22 AM.

-

2020-07-16, 11:00 AM (ISO 8601)Bugbear in the Playground

- Join Date

- Jun 2010

- Location

- Helsinki, Finland

- Gender

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Re: Paradox AAR - Saga of the Slavs

Chapter #59: The Right to Party (1852-1856)

Spoiler: Chapter1st of July, 1852

The Noble Coalition is learning that though being a protector of the status quo can be rather easy, in that it mostly requires you to just not do anything, it places you in an awkward situation when some reforms might be necessary after all. Furthermore, as the name might imply, the Noble Coalition is barely a party of its own so much as a middle road for everyone who isn’t a Royalist or a Populist. While many of its members proudly and hilariously label themselves “unideological”, claiming to just do their duty rather than push any agenda whatsoever, on the edges there is always the risk of some of them jumping ship to the other parties should the leadership somehow offend either end of the spectrum. Inaction is arguably the only thing most of them have in common, making the party’s 51% majority in the Sejm extremely perilous.